Visual effects producer and supervisor Dan Curry is synonymous with the Star Trek television series from the 1980s through the mid-2000s. It was a time in which VFX progressed from practical builds, miniatures and optical effects through to all things digital (although practical solutions certainly remained a key part of the way the show’s effects would be brought to life).

With Star Trek: Discovery about to hit the small screen, I caught up with Dan for an article at SYFY WIRE. You can find that here, but Dan and I were lucky to have a much longer conversation than the piece could allow, so I thought I’d publish the whole chat on vfxblog. Dan provided a bunch of images, as did visual effects supervisor Eric Alba, who got his start on those past Trek series.

vfxblog: Dan, how did you get into this kind of work, originally?

Dan Curry: Well, when I was in grad school, I was doing an MFA programme in Film and Theatre, and I’ve always painted. Coincidentally, I had applied and was approved to have a one man show. There was a number of small, one room galleries around the campus, and they used them for art shows. There’s a student committee that approved people, and so I had a one man show going.

By a coincidence, Marsha Lucas, who had just finished cutting Taxi Driver, was giving a seminar on editing. She happened to walk by that gallery, went and looked at my paintings, came and saw me and said, “We really need people that can do photoreal art. Would you be interested?’ She put me in touch with Dennis Muren, who was unbelievably kind, and Dennis and art director Mike Pangrazio and visual effects artist Alan Maley kind of gave me a lot of information.

I did a number of practice pieces, but I was teaching several courses. I wanted to finish my degree, so they referred me to Universal, and Peter Anderson at Universal Hartland (then a VFX facility) called me up and said, “When you’re done with school do you want to come down and work for us doing the original Battlestar Galactica and Buck Rogers in the 25th Century, and do matte paintings?”

That’s where I got my start with oils, and we had a really great guy, David Stipes, who was the matte camera operator who was incredibly generous with sharing his knowledge, as were most of the other people, and that’s when I got exposed to motion control photography, effects animation, stuff like that. We basically worked a minimum of twelve hours a day, five days a week to keep up with those shows, and that was my start.

When Universal decided to shut down that division, then I was hired by Modern Film Effects, and I became the art director there. My responsibilities were supervising visual effects, designing title sequences, doing graphic design work, and directing first and second unit. I went from Modern Film Effects to Cinema Research Corporation, and at Cinema Research, we did a lot of stuff for Paramount, so when they were starting Next Generation, they called us and said, “Would you want to come over and meet Gene Roddenberry?” and they hired me, too.

vfxblog: What were the original kinds of effects planned for TNG?

Dan Curry: The original thought was they would just do 40 stock shots and all the stories would take place on the ship, and of course that was not how things worked out. Rob Legato and I alternated episodes on Next Generation, and then that was the beginning of my relationship with Star Trek – I went on to do Deep Space Nine, Voyager and Enterprise.

vfxblog: I want to ask you about motion control photography – for someone who’s never really dealt with it because they’re so used to CGI ships, could you explain what motion control photography was all about and how it was actually used on those Trek shows?

Dan Curry: Basically, the story goes, the apocryphal story, which may or may not be true, is that Doug Trumbull was visiting an aerospace factory and looked at this giant milling machine doing the same thing over and over again as it slowly cut away chunks of aluminium, forming a piece of an aircraft. The light went on. Before that, with all the space stuff, it was impossible to get an exposure, say, for windows, and an exposure on the ship at the same time because the lights on the ship – you couldn’t put a light inside a model ship bright enough to be seen while you’re photographing the exterior of the ship.

Apparently the story goes the light went on, and Doug realised that if you repeated the ship doing exactly the same thing over and over again you could do an exposure for every element and then combine them later on in an optical printer. That’s how we did Buck Rogers and some of the great features. That’s how ILM of course did the early Star Wars stuff.

Motion control allows you to time to get a proper exposure for every element including a matte pass, which is to obtain a perfect silhouette of the ship so that you can make a hole in the background and have a place to put the ship in it. That way you can do windows and certain elements, like, say, shooting the Enterprise. For example, when we’d shoot the warp drive lights on, we want them to glow. You’d shoot that pass with a diffusion filter so that it would glow, and then we would combine everything, at least in the early days with Next Generation, with analogue tape compositing. Then a few years into New Generation, D5 came along, which changed everything because with the early analogue compositing it was like film. Every time you duped a generation, the image quality would suffer.

vfxblog: You made some in-roads into motion control shooting by using a red screen with UV light, as I recall?

Dan Curry: Yes, when we would shoot the matte passes on the ships, that was a big problem. We didn’t have the elaborate blue screen systems that were available at Disney and ILM, so we would shoot white cards, and that became a real problem because each card was at a different angle to the source of light, so there was a slightly different density.

We started out with a seven foot Enterprise that ILM built, and it was a wonderful model, but it was pretty unwieldy for the matte passes, because if we did a flyby we’d have to keep moving the cards, and it would take forever. We had Greg Jein then build a four footer, and asked him to enhance the surface detail so that there would be more different levels for light to play off, which actually made the smaller model look bigger than the seven foot model.

Then the late Gary Hutzel had the brilliant idea of let’s use dayglow orange as our background cards and use ultraviolet light, that way whatever angle the dayglow painted cards were to the light source, the luminosity was the same, so it just made all our matte passes that much easier. Because frequently the matte pass would work for part of the shot, then you’d have to move the cards to the next part of the shot, and move the cards again for the last part of the shot, so it made hooking them up and blending them together a lot easier.

vfxblog: It must have been interesting doing this also for television. People had obviously started getting used to blockbuster effects including for Trek films. What were the particular challenges of doing motion control and building miniatures, but actually doing it on television scale and budget and timeline?

Dan Curry: Well, you just hit it with the question. The challenge was the time and the schedules because the air dates were unforgiving, so we would basically have to do have a feature that they would spend a year on in seven weeks. That was the challenge as well as budget, and then storytelling. Because, say, for example, we’d have to find ways to do things that the audience wouldn’t feel cheated, and the audiences by then were used to Star Wars, and they expected that quality in visual effects, so we couldn’t get by the clunkier stuff that technology necessitated in earlier shows.

Early on in Trek, our budgets were so low that sometimes when we’d have the guest alien of the week I would make a model out of glueing a couple of toy submarine holes onto a shampoo bottle and sticking a bunch of model parts on it, and that became the ship.

It was like mediaeval alchemy, and one of the things that I think was an important factor is that we had the ability to look at things not for what they are or what their original purpose was, but for what they could be. I remember one time I had to create an escape pod, and I just went to the hardware store and I saw a really interesting sleeve to repair a sprinkler system. Once I stuck a couple of things on it and put a ping pong ball over here and did this, it would look like an escape pod. That way for 25 bucks I had a model that had we gone to a professional model builder would have cost at least a couple thousand, which we didn’t have in our budget.

We also discovered that liquid nitrogen makes great scale fire, so that, for example, if the ship is supposed to be burning and fire coming out from a hole in the hull, what we do is take a black painted cardboard box, cut a jagged hole in it, put liquid nitrogen inside, and a bunch of fans and air jets, and it would blow the nitrogen, and the turbidity would make it look like the flames, the tongues of fire. Then we would just feed fire through it and it did really good. We did a distant forest fire on a planet that way.

vfxblog: Did you guys also use cloud tanks in Trek?

Dan Curry: Yes, we did. We did indeed. We had a giant aquarium, and the trick with that was you would make different temperatures of water in it, so you’d put, say, one temperature of water, then lay a plastic sheet in, then pour another few inches of a different temperature or sometimes salt water, so that you’d have layers so that when we’d inject the paint or heavy cream or whatever material we were using for the clouds, that as it hit the different layers of different temperature waters, it would behave differently and behave more like what would happen in the atmosphere.

vfxblog: Can you talk about the evolution of the use of film and then video tape on Trek as well – that was a big change too, wasn’t it?

Dan Curry: Well, Paramount was very courageous with Next Generation in that it was the first show of its nature that did not have a film negative as the final product, and it was considered not to be done because you couldn’t archive it on film the way the studios were used to doing.

We went to a company called CIS, which was the only company that had a pin registered transfer system. The earlier devices to transfer film to video had rubber wheels on it, so the placement of each frame was not exact, and so that if you shot windows and the hull, the window lights would kind of dance over the hull, things wouldn’t register correctly. CIS basically had the best mechanical pin registrants, where they took a movement from an optical printer and put it inside. They pulled out the rubber wheels and replaced with proper film sprockets and stuff so that they would film the Bell and Howell perfs so that each frame was exactly where the previous frame would be.

Interestingly enough, a few years ago I supervised the transfer of season two of Next Generation to Blu Ray, and none of the pin registered transfer systems existed anymore, and they used little lasers to dance around in the sprockets, but they weren’t that accurate and things had to be hand tweaked to do a proper composite.

vfxblog: Let’s talk about the move to digital – what were some of the first digital visual effects or CGI things that were done?

Dan Curry: I forget the name of the episode, but the first thing was basically this giant crystalline entity that came to town and caused a lot of problems. It looked like a crystal in a piece of sage brush from the American deserts, and that was one of our first CG things because we couldn’t really make anything physical like that.

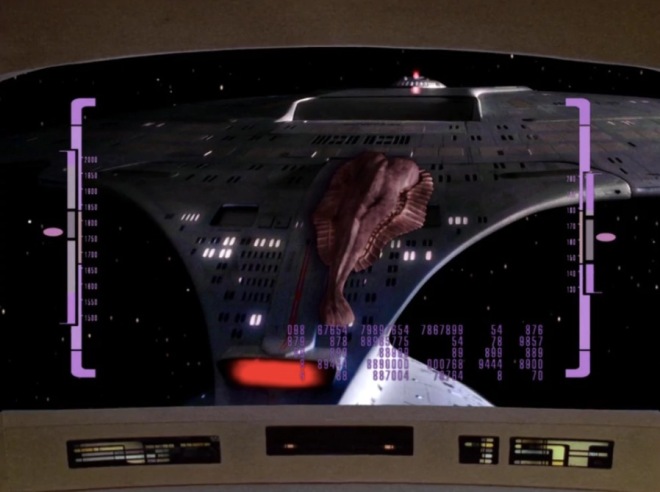

Then the other one was Galaxy’s Child, and it was our first CG creature. We had built, the great model maker, Tony Meininger, designed this creature based on a piece of plankton, which is microscopic, but thought, “Hey, that would be cool if it was huge.”

So Tony built a physical model of it with the little air bladders in it so its abdomen could kind of undulate, and it had little lights like the deep sea creatures that self-generate light. But then during the course of the story, the Enterprise accidentally kills it. We find out that it’s a pregnant creature, and the Enterprise performs a Caesarian section and saves the baby, but the baby thinks that the Enterprise is its mother and attaches itself.

When I designed the baby, I sort of it ‘Bambified’ it – this is how when Disney in the early cartoons, the babies would always have big heads and they would be really cute, so I kind of changed the proportion so it was very cute. Then it had to undulate and move around as if it didn’t become, say, rigid as it grew older, so that one, Rhythm & Hues did that CGI creature for us.

There was an episode where Geordi encountered this blob of yellow stuff. It looked like a big blog of mucus that had an undulating surface, so I forget where that came in, but that kind of lead to Odo in Deep Space Nine. Odo had to be CG, portrayed by the wonderful actor and wonderful human being, René Auberjonois.

We were a little wary of going with CG ships because the artefacts of the surfaces looked always a little stretchy, so we wound up when they wrote bigger episodes where we had more ships than we could physically shoot for a given episode, we had to go to CG. We would the use the foreground ships as models, but the background ships were CG until we felt confident enough in the look of CG to use them for everything.

vfxblog: Do you remember when you were confident enough to have a main beauty pass of a main ship being done computer graphics?

Dan Curry: That was well into Voyager. In Deep Space Nine, we did use some CG stuff, but still it was mostly models. CG was the wormhole of course and Odo, but there was only one shot of the Deep Space Nine that was CG, and that was the last shot of the final episode where we did a pullback that we physically couldn’t do with a model because we couldn’t get close enough to the model to pull the shot off.

vfxblog: Because the show wasn’t all done in computer graphics and because much of it was shot practically – and we’re not just talking about ships here – there always seemed to me to be something more real and authentic about the work. It just felt more entrenched in reality. Can talk about that side of things, from a visual effects perspective?

Dan Curry: Well, I think the fact that both the regular material and effects were shot on film, it had the same look, and film is really analogue the way it works. But I think also the fact that you can’t move the camera in ways that are impossible, because you had the physical limitations of the motion control rig.

The camera could only go, the track was only so long, the tower was only so high, the east-west was only so far, so that the limitations in a way I think lended to that, where say if you look at some of the later shows the camera flies all over the place, and no real camera would do that. I think it separates the viewer subconsciously from a level of reality because somewhere in their mind they know that that can’t happen. You don’t have a space jet ski that can move the camera around anywhere you want, though now we have drones that can do that, but in those days we didn’t have such things. The camera work had the same limitations as real camera work on set.

vfxblog: Was there a feeling at the time that you needed to match anything being done in the Star Trek films. What was the sort of interaction with what ILM or Blue Sky or other studio would be doing for a film and what was being done in TV?

Dan Curry: Well, we were all kind of fans of each other, and I think I was talking to one of the producers at ILM who was amazed that we could do what we did at such a fast pace. But we didn’t have the luxury of doing tests and stuff like that, so sometimes I look back at the old work and go, “Oh, how could I have done that?” But you had to make a decision and live with it.

But of course we respected ILM; they did the best work in the world, and they had Dennis Muren, who’s a true genius, and all those wonderful people up there. They would help us a lot too. Like, we got the Bird of Prey from them, and then when we did the finale of Next Generation, we needed a medical ship for Dr. Crusher, and Bill George had made a ship himself that he let us use as Dr. Crusher’s ship in that final episode. I think we, of course, had great respect for ILM, and I think they looked at us not like their second class relative. It was a different thing. Film is, movies are a marathon, where TV’s a sprint.

vfxblog: That era in television visual effects is considered a crucial one, isn’t it?

Dan Curry: I think the important thing is that the visual effects on Star Trek were truly a team effort, and it’s easy for the supervisor to get all the credit because you’re the team leader, the department head or whatever, but it should be noted every time Star Trek visual effects is mentioned is that everybody knew Star Trek was something greater than the sum of its parts. We all knew that it had a global cultural significance to a lot of people, so we owed it our best work.

Everybody was a contributor and a collaborator from the guys setting the models on the stand to doing the lighting, the compositors, so everybody, we were all part of a team, and it was kind of like a military operation. Each person had their job, and the people that stayed with the show or wanted to stay with the show did their jobs really well and functioned as a team. I think our whatever awards we received were in recognition in the quality of the team and the ability of people to work together.

Check out Dan Curry’s website at http://dancurrygallery.net/

Post a Comment