Why ‘Air Force One’ has some of the most talked about visual effects in history

Posted in: Animation

When Wolfgang Petersen’s Air Force One was released 20 years ago this week in 1997, it would be one of Boss Film Studios’ very last visual effects projects before founder Richard Edlund shut the effects company’s doors. The studio spectacularly delivered and destroyed a number of intricate miniature aircraft for the show. It also dived into several CG plane shots, including the scene of Air Force One crashing into the ocean, one that was perhaps not as spectacular.

That means that Air Force One is unusually remembered for both its intense and immensely watchable air-to-air sequences realised with models and live action photography, and for the final CG watery plane crash that did not meet the expectations of the filmmakers and the audience.

For the film’s 20th anniversary, vfxblog spoke to Edlund – the film’s overall visual effects supervisor (James E. Price was Boss Film’s VFX supe on the show) – to discuss the approach to the models and miniatures, the rise of digital compositing, the end of Boss, and that final crash shot. Plus, the interview includes a bunch of unique behind the scenes CG model frames from Boss’ digital aircraft.

vfxblog: Can you recall your first discussions with the director about Air Force One, and how you would use miniatures and digital effects?

Richard Edlund: I met with Wolfgang and we went over the shots and the look that he was after. At one point we were even actually planning on getting some real pilots to fly with Air Force One, which we could take off from Rickenbacker Air Force Base back in Ohio. The problem is that the pilots wouldn’t get within a mile of the plane, so that idea was out.

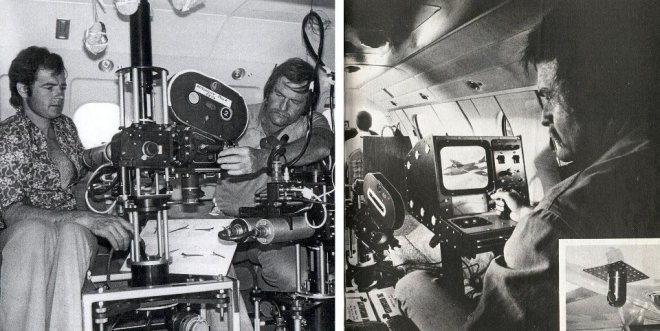

So, what we wound up doing is we created a 22-foot wingspan model, and we built a nine-wire repeatable motion control rig in an aeroplane hangar in the Van Nuys Airport and shot out there for months. Gary Waller (visual effects director of photography) did all the big model work.

About halfway through the project, the guys had built a digital Air Force One [see breakdown below], and frankly, had we started a few months later we probably would have shot all the miniature work digitally. But as it went, we had a very elaborate photographic system set up out in Van Nuys. The thing is that the way we decided to deal with the matting, because, of course, we have to be able to create a matte of the plane, and what we wound up doing is using a red screen and blacklight to extract the background.

vfxblog: How did that approach to shooting the miniature with that matte system work?

Edlund: In order to get rid of spill, we had to spray talcum powder all over the model after each shot. So in other words, we would do the shot, do the beauty pass, and then the next day we would have to spray the model with talcum powder and then shoot it against a red screen. Then we had to clean the model off of all the talcum powder in order to do the next shot. Of course that meant that the shooting stage was sort of like a skating rink. It was so slippery. In fact, actually, I tripped and wound up with a hairline fracture in my foot once.

Anyway, that was quite an ordeal shooting all those models. And we also wound up shooting in 35mm, so we were shooting 35 and scanning it at high resolution and doing the composites back onto 35, which was the release format.

vfxblog: What did that red screen approach give you that maybe green screen or blue screen wasn’t suitable for?

Edlund: I think the whole idea about being able to expose it with blacklight was the key, and we were able to get enough exposure and not have to … again, we would have had to deal with some sort of green spill or blue spill problem, and the talcum powder technique worked out really well for us. I think we were able to get a larger screen and get enough exposure to shoot a reasonably exposed mat.

And then this nine-wire rig was pretty amazing. So there were nine points on the ship that went up to pulleys. The wire did not stretch. In other words, it was very, very tight wire, and we were able to do repeat passes with this 23-foot model, which could bank left and right about 45 degrees, forward and aft up to 90 degrees, and it was really an amazing set up; built for the shot, and then torn down, and never to be used again.

vfxblog: I seem to remember the plane model had been used earlier for Turbulence – was there much cross-over?

Edlund: Well, actually, the model was built for Turbulence, and we actually rebuilt it and tricked it out to the nines to the point where they were actually using paint thicknesses to create the plates on the ship. It was really a beautifully made ship, and it was hanging up in the Museum of Flight up in Seattle. We donated it to the museum when we were finished shooting.

We also built the big model that Harrison hung out the back of. God, that was quite a scene. A lot of that stuff was actually shot with Harrison in the model, or in the full-size ship. Then we built the refuelling ship, which then had to blow up. We built that and shot that in a parking lot outside of the stage that had the big motion control rig set up. We also built a bunch of F-16s, and we got into compositing with Wolfgang, and Wolfgang would get so fixated on that.

vfxblog: Can you talk more about what you mean by ‘fixated’?

Edlund: One of the problems, I guess, with digital compositing, is that you can continue to do it over, and over, and over, and over, and over again to the point where you’re doing something over in order to correct something that is so minuscule, and the director gets hung up on one little detail of the shot; you wind up doing the shot over and over again to try to satisfy the brightness of the trailing lights. In other words, ‘This is not quite bright enough.’ And we’d make it a little bit brighter and then, ‘That’s too much.’

It was kind of exasperating to go through the numbers of composites that we could do. That’s just because you can. You can continue to do it over and over again. And the director will continue to ask for it over and over again, whether or not it’s reasonable. So you become kind of threadbare after awhile doing these shots. It was a tough project.

Then, of course, there was the tumbling of the ship in the water and that whole business that was kind of only semi-successful. I don’t know how that feels to you today.

vfxblog: Well, I was going to ask you about it [watch the clip above]. I feel like the problem seemed to be that you had these beautifully detailed miniatures and then that CG plane and the interaction with the water probably isn’t as successful.

Edlund: Yeah, that was a real nightmare for us. We couldn’t get it more than maybe 80% of where we wanted to get it, and we just ran out of time. Some of the time that we spent doing those composites over and over could have been towards this, but it wasn’t. We kept working on it. They were working overnight, and they were sleeping there, and doing whatever they could to make it better, and what we got was the best as it could be. Anyway, it was bittersweet project.

vfxblog: I don’t want to keep asking you about it, but you’ve worked on lots of films, and you’re probably very hard on your own work. Where is the point where a director says, ‘Well, it’s just got to go in the movie now.’ What is that like?

Edlund: Well, when you have to cut a shot in that sucks you feel bad about it. You know? I mean, one of the worst shots of all time was in Star Wars. It was when Gary Kurtz put the camera where he shouldn’t have put it so we could see all the tyres underneath the land speeder. In order to get rid of that tyre, I had rotoscoped an area and we were working on perfecting it, and I was shifting sand from the left over to the right that would match, and we had just a very fine little matte line, and we were just about ready to close in on it, I think maybe one or two more composites and we would have got it, but George decided that he was going to send it to Disney and have them ‘blob’ it.

So they rotoscoped and painted the area with as close an approximation of the colour that they could, and it wasn’t very good. In fact, it was so bad that when the movie came out and that shot was about to play I would nudge whoever I was with so they could look away from the screen and not notice the shot. When George came out with the Special Edition I went to the premiere down in LA that they had at the Fox Village Theatre, and I was talking to George and I say, ‘You know, George, we’ve heard all these rumours about: ‘This is going to get changed, and they’re going to reshoot the opening shot,’ and all this kind of stuff…and I said to him, I said, ‘This is your movie, you can do what you want with it.’

And he says, ‘You know, Richard?’ He says, ‘Do you remember that shot of the land speeder?’ And I said, ‘Oh, say no more.’ And he says, ‘Well, I couldn’t release the movie with a shot like that,’ he says, ‘but then we got carried away.’ Which I feel is the case. I mean, a lot of those scenes were just so over-polished that they kind of buggered it to some degree. But anyhow, I thought that was an interesting confession: ‘We got carried away.’

vfxblog: Can you take me through the the backgrounds for the model shots in Air Force One, because there are some great skies and clouds?

Edlund: All those air-to-air shots were motion control shots; every single Air Force One model shot was a motion control shot. We did all of the shots before we had backgrounds. So basically what I did is I went out with this Nettmann Cam-Remote system – it was a snorkel system that stuck out the bottom of a Learjet, and we mounted motion control motors onto the pan, tilt, and roll axis of that system, and went up and just luckily had this fantastic day where the weather was perfect.

A side note is, the copilot was Gene Kelly’s wife. And she was a dancer. So she basically had control of his heirs, I mean, she was the heir to his fortune. She was getting hours to get her pilot’s licence, and she was the copilot. Very funny. She had this very slick Dior-fashioned jumpsuit. She was all decked out to the nines.

Anyhow, I shot all of the plates for the backgrounds in less than 400 feet. So I came out of the plane with less than a 400-foot roll of film with all the shots on it. I mean, normally you’d go up and you’d shoot, like, thousands of feet, and then you’d hope that you could find something that would work, but this time it was all motion controlled and we had such great weather for the day, and that was a real positive thing. And the composites, I think, looked really good as a result of that.

vfxblog: How was that tanker explosion you mentioned filmed?

Edlund: We basically had this big model, and the model had, like, it must have been a 40-foot wingspan or something like that; great big model held up by wires with two great big condors that were 100-feet tall. So we were shooting straight up at the model, and Bill Klinger set up the pyro for this. We basically had the camera looking straight up running at 270 frames a second, as I remember, and when the truck drove over the switch, it exploded the plane. And, of course, we only had one take on this, and we got it. It was a great shot.

vfxblog: There were also some fighter jet explosions that I just thought also worked really well. Was that a similar approach?

Edlund: Pretty much. It was all setting it up and driving by it and blowing it up. We built a whole nest of those things. I think we built, it might have been at least a dozen of them, and six or seven of those, or maybe eight, were built for explosion. So we blew them up. I mean, it’s fun to blow things up, you know? It’s just, the pressure gets a little tight though, you know, because you don’t want to fuck up.

vfxblog: Unfortunately, after this film came out you had to close Boss, and everyone was so disappointed, but I also felt like you did that very nobly before it got out of control.

Edlund: Well, I had the choice of doing that. The thing is, I looked out over the landscape. And being an independent company, which is nonetheless dependent on landing multi-million dollar shows just as the last foot left, you know, the next foot has to hit the pavement. If you don’t hit that pavement pretty quick, you’re going to be in deep shit.

So basically, I looked out over the landscape and I thought, ‘You know what? I don’t want to show up here one morning with a padlock on the gate.’ And that’s what might have happened had the company gone bankrupt. And had I not been able to close a show and had to then reach into what little reserve we had, it wouldn’t last long enough to pull us out.

So I decided to close gracefully and that’s what we did. So it was sad, but we had a 15-year run, did a lot of great shows, and had great times. And a lot of the people that worked at Boss still feel that it was their best years. I mean, everybody enjoyed each other’s company. People tried to come in and steal people, and they wouldn’t go. People would call in and say, ‘Hey, do you want to work on this show?’ And they’d just hang up on them because they were happy within the family we had created.

Post a Comment