Illustration by Aidan Roberts.

At some point in early 1996, cinema-goers saw a teaser trailer for a new Jan de Bont film called Twister. In the Warner Bros. teaser, a family takes shelter during a roaring tornado. Scary enough on its own, the teaser dramatically took on ‘epic’ status when a short scene of even greater chaos suddenly popped up for a only a few seconds at the very end – enough to reveal a destructive tornado scene complete with a disintegrating barn, a flying tractor and a tire that smashes into a vehicle windscreen through which all this insane action is being viewed by the audience.

It has become one of cinema’s classic money shots, a wow moment, and all the more incredible for the fact that it does not actually appear in the final film. However, the chaos and destruction of that scene was orchestrated by Industrial Light & Magic (ILM), which would go on to also deliver some of the most technically advanced and convincing tornado, environment and destruction effects for the full feature.

And, a flying cow.

Above: Twister’s theatrical trailer includes the classic tire shot right at its thrilling conclusion.

More on that test shot and the flying cow later, but first let’s recognize the milestone that was and is Twister. Released on May 10th, 1996, the Jan de Bont pic was immediately a box office success and would go on to gross around $494 million worldwide. Part road movie, part ride movie, Twister’s tale about rival and determined storm chasers in Oklahoma made the most of De Bont’s experience as a director of photography on such gritty actioners as Die Hard and The Hunt for Red October and his never-slow-down filmmaking style established as the director of Speed. If Speed was to forever be known as ‘the bus movie’ then Twister equally became the hallmark for any storm and tornado film that followed.

Just how do you make a tornado?

Although full of large scale practical effects, Twister would simply not have been possible without its photorealistic titular characters – the tornados. And these were expertly crafted in computer graphics by the team at ILM, still fresh from the CG milestones achieved on films like Terminator 2 and Jurassic Park. Leading the team was Stefen Fangmeier in his first sole outing as visual effects supervisor.

A background plate including ILM’s wireframe tornado and barn for one of the early dramatic scenes in Twister.

Fangmeier had previously worked on T2, Hook, Jurassic Park, The Mask and Casper before getting the call-up on Twister from one of ILM’s most experienced visual effects supervisors, Dennis Muren. The senior VFX supe has earlier collaborated with producer Steven Spielberg on the stunning 400 frame POV test shot. “I wasn’t along for that test,” recalls Fangmeier, “but Dennis had the camera operator sit next to the driver in this truck out in Novato, California where he found a dusty road that approximated the film’s Oklahoma locale and then they would be driving along and swerving about. Ultimately all the debris was CG and it had this very hand-held feel which was important to Jan and Steven to represent how people might shoot a real tornado in that situation.”

Fangmeier was involved with, however, crafting the digital tornado in the test, along with digital tornado designers (yes, that’s the actual credit) Habib Zargarpour and Henry LaBounta. It helped, too, that Fangmeier had tinkered with the tech behind synthetic twisters in a previous job.

The final shot of the barn being destroyed by the menacing twister.

“I was working a the National Center for Supercomputing at the University of Illinois,” he relates. “The researchers were using a Cray supercomputer to come up with simulations. Some were scientists in meteorology and they were trying to simulate how tornados were formed. So in 1987 I did some visualizations for these tornado chasers – they were very simplistic shapes, but we computed them in a 3D volume and showed the tornado forming. Then eight years later I was helping do it for the movie.”

Particle fever

If there had been any hope that real tornados might be featured in the film, that was quickly dispelled during principal photography when the filmmakers tried to chase actual twisters, with no luck. The task would fall to ILM completely, and with both filmmakers and audiences hungry for more photorealistic CG imagery after those early-90s CGI breakthrough films, the twisters in Twister would have to be a significant step up from any previous CG simulations or other tornados heretofore realized on screen.

That meant ILM had to make major in-roads into effects systems that would help bring the tornados to life – at the time still an extremely difficult proposition to control and render realistically. Also, up until that point ILM had mastered creatures and hard surfaced CG objects, not the particulate nature of a twister. “A tornado is a ton of dirt and dust in a swirling mass along with moisture and cloud matter,” notes Fangmeier. “That makes particle systems really the foundation of a tornado.”

Above: Stefen Fangmeier breaks down some of Twister’s VFX in this video from the film’s home entertainment release.

Even though ILM was pushing for absolutely photoreal tornados, Fangmeier knew that whatever they produced in CG with a particle system could still only be an approximation. “You can’t really model the complexity of nature and reality, well, you couldn’t back then. In a tornado there would be an uncountable number of particles in a volume that the computer would not have the resource to simulate. So we had to make it look like the kind of level of detail that was in a tornado.”

To work out that level of detail, ILM gathered reference, which, unfortunately, was generally poor quality. “I learnt a tremendous amount about the science first,” says Fangmeier, “but then the reference was only low resolution video. No one had been out there with a 35mm camera being able to capture a tornado.” There were, however, nicely detailed photographs available and for the largest of the tornados, the F5, ILM could establish the different layers required and the different cloud looks for inner and outer areas.

Above: Today’s digital video cameras and phones are capable of capturing high-res reference of tornados such as this recent twister near Wray, CO – not something that was available for the ILM team at the time of making Twister.

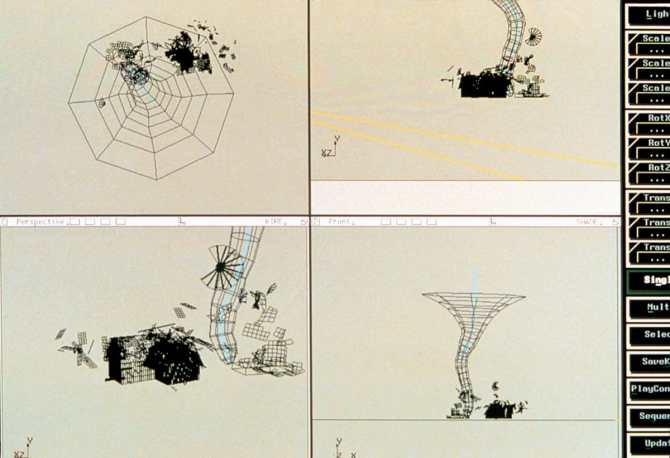

With the reference that could be acquired in-hand, Fangmeier’s team embarked on a series of custom plug-ins for the 3D software ILM was using at the time (specifically, this was a custom interface for Wavefront’s Dynamation, while animation was also handled in Softimage3D). The basic shape of a tornado ranged from between 5 and 10 million particles. Animators would actually first choreograph the general movement of the tornado with what was effectively a hollow funnel that could be twisted and turned, but then with so much dirt and debris and destruction to co-ordinate, that part of the effects had to remain a simulation.

Still, Fangmeier needed a level of control – it was a fantasy movie after all and the twisters were art directed to be overly menacing. “Scientists might find the randomness interesting, but we have to say, OK, the tornado has to move over here at this speed and we have to know what will happen. So in the end it was a combination of animation and controlling the simple parameters and then the chaos of simulation that allowed us to get the visual complexity, so that it looks like it’s chaotic. You learn the science and then you say: it’s a movie.”

Destruction, destruction, destruction

The twisters, of course, wreak a whole lot of havoc. From lifting cars to whole petrol tankers and smashing through barns, the particle effects simulations ILM had developed would also have to interact with solid elements and disintegrate them. Initial talk of building some of these elements as miniatures was quickly dismissed by Fangmeier.

Special effects supervisor John Frazier orchestrated many full-scale destruction effects for Twister.

“All these things had to interact with this force and I quickly decided that, well, we’re not going to use miniatures at all for that, because it just won’t look right. There’s nothing you can do to make it look right in terms of ripping it apart. So we decided early to build all these objects in CG and have them properly interact with lighting and being matted against the tornado so it would disappear or re-appear.”

The debris was a complex mass of particle simulations and hand-animated pieces, sometimes in the order of 10 to 20 thousand-fold. Animators actually had fine control of hero pieces of say a barn that was to be ripped apart – itself a structure of about 3000 pieces that would then be released into the forces of the tornado. ILM’s debris, too, had to match to what had been achieved on location by special effects supervisor John Frazier.

A screenshot from Softimage of the tornado spline and barn wireframe.

“He had come up with a rig,” explains Fangmeier, “which was actually a jet engine on a back of a flatbed trailer – a full 16 wheeler massive truck. Well, that lasted about two days because he blew so much debris into these scenes that the actors quickly got eye infections! So we were going to add a lot of that debris in CG in post.”

Freedom to move

Solving Twister’s computer graphics challenges turned out to be only half the battle. Jan de Bont had made it clear early on he wanted to shoot the movie from the perspective of a tornado chaser, and that meant going hand-held for many, many shots – an added complication to ILM’s incorporation of the CG twisters into the live action.*

Actors Bill Paxton (left) and Helen Hunt with director Jan de Bont.

“What was unique about Twister at that time was that essentially we weren’t able to use any bluescreens at all,” adds Fangmeier. “We were in moving cars, shooting out through the windows, or we were running in a field with a handheld camera.”

This turned out to be Fangmeier’s preferred approach, since it meant that the visual effects shots did not feel, as he puts it, ‘stagey’ and it meant they could exist in the same frenetic world as the rest of the film (ie. visual effects could cut directly against non-effects shots and feel the same).

Shooting a road scene with practical water jets and debris.

“We just gave Jan the freedom to do whatever he wanted with the camera to keep it dynamic,” says Fangmeier. “We had rain on the windshield, too. That’s usually a nightmare to composite CG things through. But I said, put the rain on there, put the wipers on there – we’ll figure out later how to put the stuff on the other side of the windshield. I let him shoot it as naturally as he could and our incredible compositors did a pretty great job of integrating everything.”

There were limits, though. At one point the camera department fitted out the film cameras with specialized shakers, essentially drills, that would make it appear as if a lot of wind was impacting on them. “I said to Jan after a couple of days of filming – please don’t do this,” recalls Fangmeier. “I’ll add the camera shake in post. If you do this here the matchmove is already tough enough that it will be even more challenging. He stopped using them after that.”

Indeed, Fangmeier was perhaps more up front with De Bont than other filmmakers had been able to achieve. “I got along with Jan quite well. He had a reputation of being a bit of a bully and ruffian but if a director understands that he or she doesn’t have the knowledge that you have about something, they’re quite collaborative. Jan was smart enough to know that he needed to have a good relationship with me in terms of getting this stuff done. Him being Dutch and me being German probably played a part in it too.”

‘We got cows’

If building tornados, destroying buildings and integrating all of these elements into constantly moving shots was not hard enough, De Bont still had one incredible task left for ILM: that flying cow. This memorable scene, as absurd as it appears, was perhaps not so fantastical. “It was based on actual real occurrences,” points out Fangmeier. “Farmers, after a tornado had gone through, were reporting finding their cows miles and miles away from the field where they had last been.”

“The thing is,” continues Fangmeier, “nobody had ever videotaped a cow flying through a tornado. We were shooting this from a moving car. It’s not like we put a cow on a cable and floated it through the air to see what it would do. We just did a guess of what it would look like. How would an animal suspended in the air look? It’s not running, OK. Maybe its legs would be slightly tucked in and it would probably be lost so maybe it’s twisting its neck. There was that element of comedy in there.”

Illustration by Aidan Roberts.

The landmark effects work in Twister was rewarded with an Academy Award nomination for Best Visual Effects (for Stefen Fangmeier, John Frazier, Habib Zargarpour and Henry La Bounta). Although Independence Day ultimately took out the prize, it was clear that ILM’s work on the tornados and surrounding shots in Twister continued to cement the studio’s dominant reputation as an innovator in the industry.

“After Jurassic Park happened, we really broke the mold of putting digital effects at the forefront,” says Fangmeier, who went on to be a visual effects supervisor on films such as Saving Private Ryan, A Perfect Storm and Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World before directing Eragon. “So much so that all the clients said, ‘We don’t want the traditional ways – we don’t want miniatures, optical composites – we want this new-fangled digital thing.’ And it spurred us on to do all this great work there, of which Twister was a big step.”

For more on Twister check out:

Warner Bros. Twister page: http://www.warnerbros.com/twister/

ILM’s Twister page: http://www.ilm.com/vfx/twister/

VFXHQ Twister page: http://www.vfxhq.com/1996/twister.html

Banned From The Ranch Twister page – on-set CG graphics and playback (hosted by VFXHQ): http://vfxhq.com/bftr/projects/twister.html

Cinefex #66: http://www.cinefex.com/backissues/issue66.htm

Art of the Title on Twister’s opening titles: http://www.artofthetitle.com/title/twister/

Ars Electronica 1997 Twister entry – includes ILM info, video, pics and PDFs with ILM credits (check out some of the famous names): http://archive.aec.at/prix/#31260

*Editor’s note: Matt Wallin, who was a rotoscope artist at ILM on the show, tells vfxblog, “I think we were still using Parallax Matador for roto. It was one of the early shows to make use of iComp which later became Comptime. This was the in house tool developed at ILM.”

Back to vfxblog.com

Post a Comment