Before you see Tom Cruise’s ‘The Mummy’, re-visit the digital make-up, mocap and other VFX innovations from the 1999 film

Posted in: Animation

You’ve got a character that needs to be desiccated and completely non-human in its position but has to be believably human in the way that it moves. Well, that’s motion capture in a nutshell. – John Berton Jr., ILM visual effects supervisor, The Mummy

In 1999, director Stephen Sommers’ The Mummy burst onto cinema screens with visual effects from Industrial Light & Magic. The film’s fun-natured approach to what had previously been a horror genre of ‘mummy’ films was welcomed generously by audiences. As were ILM’s VFX, which took advantage of new approaches to motion capture, particle sims and CG.

The visual effects supervisor was John Berton Jr., who would go on to supervise the film’s sequel, The Mummy Returns, and Men in Black II at ILM, before becoming a freelance supe on films including Charlotte’s Web and Bedtime Stories. He is now a visual effects supervisor at Lytro, exploring the world of light fields.

With a new Mummy film about to hit, vfxblog went back in time with Berton to see how ILM conquered then-new challenges and how visual effects were very much part of the storytelling process in Sommers’ adventure. And in a special bonus addition to this interview, ILM’s visual effects art director on The Mummy, Alex Laurant (now principal art director, Microsoft / Windows Experiences), has generously provided a wealth of concept art, storyboards and other imagery from his work on the show.

vfxblog: There were so many different types of effects ILM was called on to create for The Mummy, and a lot that hadn’t really been done before. What were some of your first conversations about how you would approach the film?

John Berton Jr.: Well, one of the things that I think kind of defines what the aesthetic of the 1999 Mummy was, was that when Stephen Sommers came to me with the idea of doing The Mummy, the first question that he asked me, or really the first question was, ‘What should I avoid? What can’t I do? I don’t want to propose things that we can’t afford or that are impossible to do or put us in a bind.’ And I said, ‘Ignore that. Give me what you got. Give me everything. Give me every idea you have. Just go to the top,’ which was a dangerous thing to do with Stephen Sommers as it turns out, because he’s really good at going to the top. But I stand by that. And the idea was, put it all out there on the table and then we’ll discuss what we can and can’t do. But if you try to restrict yourself in the very beginning with some sort of assumption about what is or is not possible, you’re not taking advantage of the power of visual effects, and you’re surely not taking advantage of the power of digital visual effects.

And so, I think that, in a way, was an important moment because I think it set the stage for what would be designed to be in this movie. As a kind of adventure arc, there’s no ceiling here. Obviously, when it’s too big and it’s too much, that’s gonna be something that will have to be compromised elsewhere because of the realities of the world, but let’s put the best ideas in the movies and let’s put our best efforts towards making those best moments. And I think there’s a lot of things in The Mummy that maybe wouldn’t have gotten in if we hadn’t been as brave as we were in designing what this movie could be like and being courageous enough to chase those things and put them in the film.

And then that is just logistics, trying to figure out how to get it into the financial box, but you’ve got a good idea and that’s the important thing, is that you got a good idea. And then, how much money it costs to achieve it is just a measure of how glossy it is. But, a good idea doesn’t need much gloss on it. It just needs to be in the movie and work. And that’s, I think, a lot of what you see in the best visual effects movies isn’t necessarily that they’ve got the finest polish, but they have the best idea and the best execution of that idea.

vfxblog: How did you come to that view?

John Berton Jr.: I would say I learned that on my first movie, which was Terminator 2. I did a shot where the T-1000 is thrown into the wall and morphs backwards through himself and comes off the wall and returns to fight with the Arnold Schwarzenegger Terminator. Okay, well, that shot wasn’t particularly difficult from the standpoint of digital manipulation. It required many weeks of me morphing it to be at exactly right, but the idea was so great that just pulling it off was half the battle, if not more. And there, you’ve got something where that’s a memorable shot in the movie, as there are many others of course. But that’s the idea, that it’s all about how good the ideas are. And there’s a lot of stuff like that in The Mummy as well that has that same shine on it, that you might not look at and say, ‘Wow, that’s an incredibly complicated thing to do,’ but it’s whether or not it’s telling the story the way you need it to be told, and there’s just tonnes of stuff like that in The Mummy.

vfxblog: So, what I’m calling the ‘digital makeup’ on Arnold Vosloo’s character, where parts of his face are missing – did you call it digital makeup back then? Can you talk a bit about the challenges you had just with designing those and coming up with a solution for them?

John Berton Jr.: Well, the first thing about designing them was that we let our art directors off the hook. And this was all part of the same thing, it was just speaking up that there was no gag too big and nothing was off the table. Draw it, paint it up, let’s take a look at it, and then we’ll talk about how we might go about doing it. With the shots we’re actually using a live-action base of Arnold Vosloo with digital makeup. It’s kinda funny, but we never thought about it that way. It was too complicated to throw some name on it like ‘digital makeup.’

We were just trying to make the shot work. And so, this required an unbelievably complex amount of tracking. We had some tracking markers on Arnold’s face that were definitely helpful, but we didn’t have any of the complex tracking tools that you can get off the shelf with Nuke these days. Not that doing complex tracking is any easier, particularly, than it was then, but we had to do all that kind of by hand, if you will. People were writing algorithms and hand animating the CG to match onto the tracking markers. And there’s a tonne of compositing that went into locking it all down.

After that, now you’re trying to just make sure that you’ve got the right kind of shaders and the right kind of blends. And the guys that wrote the programmes at ILM in those days, and the CG supervisors like Ben Snow and Mike Bauer that were involved in creating that stuff just really went to the top of the rocket to try to make sure that everything was lined up exactly right. And those are hard shots, but they had payoffs.

If you think about the big motion control shot where Vosloo is revealed for the first time and he’s got that big hole in his cheek and the scarab runs into his mouth and he eats it. That shot was just insane with all the things that were in it, and that payoff is what makes that shot work so great. And it’s not gonna fly if you don’t have the tracking right, and that was a hard thing. And nobody knew how we were gonna do that. We put the tracking markers on there, we did our best to take as many notes and as many reference pictures, and everything that we could do to make that shot work.

And all of that information that we collected was utilised, and that’s what makes it all work. And that, I think, is part of what it is. It’s really that attention to making sure that you understand that your shot is on the day when you’re shooting it, and you understand what the story point of that shot is gonna be and where the important bit is.

Above: Various concepts for Imhotep’s stages of regeneration and decay, by Alex Laurant.

In a certain way, it’s kind of the classical situation where if you want an effect to work really well, you make sure it’s in the same frame with the principal actor. In this case, it was actually attached to the principal actor, and that’s very compelling. And that was what went on with that shot. That particular shot had a motion control underpinning to it, which was incredibly hard to shoot. And it was one of the few motion control shots we actually did on The Mummy, because it was so complicated.

Normally we shot poor man’s motion control, ’cause I prefer to shoot it that way because it just keeps the production’s flow going well and we can get good operators to stay close enough to the marks that we can stabilise it into place and we can make it work. And that was extremely successful throughout The Mummy. But in that shot, we had too much going on and we also had particle systems that were also very new. That was very nascent technology. We used the particle systems to do sand. We had practical sand that we comped into those shots, and we had our shadow composites, there was a dummy, there was a CG representation of the dummy. There was just a tonne of stuff in that shot.

And all’s the payoff with the scarab animation that was harking back to the scenes that we’d seen previously, the famous scenes with Omid Djalili being attacked by the scarabs are then reprised as the payoff on this set piece. And that was a great shot, really, really hard to work on and a tonne of different things involved. The tracking was just part of the mix. It was one of the hardest things to do, but it was only a part of that whole shot.

vfxblog: Obviously another part of the production was incorporating motion capture into the mummy character. It was still still early days in utilising motion capture, so, tell me about that and where that as a technology was up to at ILM?

John Berton Jr.: We were really out in front on that. I was fascinated by the idea of motion capture. And the thing about motion capture, that I believed then and still believe now, is that it’s great if it’s applied at the right place and the understanding of it is an understanding of its artistic possibilities rather than its financial benefits. Any time you talk about motion capture, even today, people go, ‘Oh, it’s so much faster than doing animation.’ It’s like, Nah, not so much.’ What it is, is it’s better at getting really good, photographic, real-type animation, particularly of human beings because human beings are relatively easy to strap dots on as compared to aliens or horses. So, you can get really great animation out of it.

And as we were discussing motion capture for The Mummy I was saying, ‘Okay, well look. Motion capture’s gonna work great if we have a humanoid character where we can use their motion to map something else onto that framework.’ Well, you’re not gonna find a better opportunity to do that than The Mummy. That’s perfect. You’ve got a character that needs to be desiccated and completely non-human in its position but has to be believably human in the way that it moves.

Well, that’s motion capture in a nutshell. That’s a perfect example of what you’d use it for, because there’s no translation of the data onto a nine foot alien or onto some other creature. It’s just a one-for-one. So, you’re capturing animation and trying to get that motion to the highest fidelity that you can get it. And the motion capture algorithms that were being developed at ILM by the team there, Seth Rosenthal and Jeff Light and those guys, were really putting this all together. And I was looking at it and going, ‘This is perfect for The Mummy. We gotta do this.’

And you know, the animators at first had some resistance to that idea, but as I was explaining to them how it was gonna work they really turned a corner. Daniel Jeannette, particularly, was the animation supervisor on The Mummy, and he came in to work for us on Casper, and was a classically trained animator. And he saw the possibilities the same way I did, and today you will not find a more technically-savvy, brilliant, creative animator than Daniel Jeannette, because he really took that ball and ran with it and did terrific work, along with the whole rest of the animation team, to take this captured data and turn it into a completely believable performance.

There’s one other aspect of this that’s critically important to the whole thing and why it works, and that is that I demanded that Arnold Vosloo do the capture. I said, ‘Look, everybody thinks with motion capture, just get the janitor to do it. Well, we’re not gonna do that. I want Arnold Vosloo to do the capture because I want the mummy to be walking the same way that Arnold Vosloo walks.’ And believe it or not, people can see that in an instant. You can take anybody you know and put them in a motion capture suit, and take someone you don’t know and put them in a motion capture suit, doing the exact same action, watch the stuff on a monitor with dots and lines, and you’ll be able to instantaneously pick out the person you know, because their gait is as unique to them as a fingerprint. And I said to Stephen, I said, ‘Look, you know, you wouldn’t use a double on a hero shot like this, right? The reveal of the main character, you’re not gonna use a double for that if you’re shooting it in live action. Why would you use a double if you’re shooting it in motion capture?’

And he understood what I was saying and came and directed those scenes. I said, ‘You need to be there. You need to direct Arnold in the motion capture, because you’re the director of the movie and he’s the principal actor in this instance. And this is live action. This is frontline stuff, and just because it’s hiding behind a computer graphics effect doesn’t reduce its importance. So, let’s do this right and let’s make sure that the animation on the mummy really is Arnold Vosloo, because he’s doing the actual capture. And we were really, really strict about that, and every shot that you see of the mummy in both The Mummy and The Mummy Returns is Arnold. And I think it’s one of those things that, when you’re watching a movie, you’re gonna look at that and you won’t necessarily be able to say why you’re believing it, but that’s part of it.

And if you took that out, then it wouldn’t be as good and people would be in their heads going, ‘Yeah, there was something fake about the mummy. There was something not quite right about it.’ And they wouldn’t be able to tell you what it was. But in the case of the way we did things on The Mummy, we didn’t have that problem. It was absolutely the same actor. His motions are captured accurately, and that’s why the mummy is so good in his performance, is because it’s Arnold. It’s Arnold Vosloo that’s performing that. And we maintained that performance all the way through to the final product, and that’s why you believe the mummy is him.

I’m proud of having done that, because I know in a lot of other movies, recent ones as well, people tend to try to go for the sort of financial impact of not having to pay for a principal actor. You know, if it’s just gonna be this big creature that’s lumbering around, I don’t need to capture some expensive actor. I’ll just get somebody that knows how to lumber around. Well, that’s not gonna get you as good a result as using a top-line actor. They’re a top-line actor for a reason. And most of the big movies understand that and do it, but we pioneered it on The Mummy. That’s one of my prideful statements about the work that we did on The Mummy, is that we showed how important it was to treat the animation data that you’re getting through motion capture with the same respect that you treat every performance by a principal actor.

vfxblog: In addition to the mocap, was there also a study done of the human anatomy involved? These days that would be a given, but what did you do at the time?

John Berton Jr.: Yes, if you want people to believe that your synthetic object is real, you have to approximate the complexity of reality in some form or another. In this particular case, there were many different things that we did. The first one was the overall complexity of the geometry. We did do many, many studies of human anatomy and where do muscles need to be, and what sorts of things might be lounging around in the abdominal cavities of people that have been laying around in a tomb for 5,000 years. That’s fun research, right? So, we did a lot of that stuff, which was kind of entertaining. I mean, I’ll come back to this, but one of the things that I think is wonderful about that movie is that this was not ILM’s kind of movie from the beginning. When people said, ‘The Mummy,’ they were like, ‘Oh, I don’t know. That’s not the kind of movie that we like to work on.’

But I found a group of people who did like those kinds of movies, because of course the visual effects business is packed full of them. And so, we had a crew that really understood what we were trying to do, and they were like, ‘Yeah, you know, let’s go for it. Let’s get some bandages flying around, and, God knows what’s in his guts, some lumpy, horrible stuff. Let’s see what we can do. Let’s get some reference.’ That was really wonderful time. And yeah, that’s what it was all about, was finding the right kinds of reference and finding the right kinds of complexities to put in there. So, now they’ve got the motion capture driving. Now, how do you take that and pay it off with even more complexity? So, now you have dynamic simulations that are driving the muscles, that are driving the flying bandages, that are driving the sloshing around guts inside the mummy’s chest. All that stuff’s being handled as a combination of artistic direction from the animators and procedural systems hanging of the back of that.

So, you’re starting out with a procedural system, the motion capture. You’re bringing an artist into the middle to direct where that stuff is all gonna go, and then you’re using another procedural system on the backend to add in complexity of motion. Okay, that’s part A. Now, part B is complexity of image. So, we’ve got all the models and the geometries and all that stuff. That’s adding complexity. But now, texture painting. And this was another breakthrough on The Mummy that was really exciting, is that we started doing texture painting that was much more complex than anything we had done before. And the idea was that you really couldn’t model everything that you wanted to model at that level of detail. And, of course, we had a tonne of painters who knew about organic painting, and medical illustration, and all this kind of stuff, because we hired them to come up with things like dinosaur skins, right? And so, they were there, ready with the talent to paint all kinds of complexity into what we were putting on the surfaces of our mummy bits.

And that’s why the mummy looks so awesome, is because he’s just covered with these complex textures. And that prevented us from having to do incredibly heavy, complex modelling, and that made it possible for us to render the mummy the way that we did. That was a bit of a breakthrough there, to see how far we could push textures as drivers of geometry. We used the textures not only as colour information, but also bump maps, and displacement maps, and all kinds of stuff, so that the real modelling was done by the texture painters, even more so than the geo modellers that built the substrata of everything. So, those three things working together are what really made the mummy gooey, and amazing, and fluid, and real, was taking this idea of, ‘Where can we keep adding complexity?’

We can add complexity into the motion by using dynamic simulations. We can add complexity into the look of the mummy by adding textures and colour and very complex sub-polygon modelling as achieved of textures. And those textures also define all the holes. So, there were transparency maps that were painted so that you could see through the mummy at various points in time. And that all just followed along with every … Just gave it this terrific look of a ripped up guy who was just barely hanging together by the threads. And that one turned out to be really compelling.

vfxblog: This was breakthrough stuff in motion capture but a couple of months later, Phantom Menace did come out. And I know productions stand on their own, even at ILM, but was there much discussion there about how Jar Jar was being motion captured or keyframe animated, and about how Arnold was being done?

John Berton Jr.: Well certainly, the motion capture guys were seeing both sides of the equation. So, those guys that I mentioned earlier were doing the motion capture for both movies. So they knew what was going on and how that was playing out. The animation directors on Star Wars, of course are great friends of mine as well, so we talked all the time about how to utilise this stuff effectively. And Daniel, as well, was talking constantly with those guys. There was a lot of crossover. I wasn’t in any way involved in what was going on with Jar Jar, but at the same time, all of this knowledge that was coming through ILM at that time about what’s working and what was working best was certainly crossing back and forth.

I think we were a little bit out front on that. I certainly didn’t have any information that I had from the Star Wars crew when I started shooting The Mummy, because Star Wars was being done in a completely different way than the way The Mummy was being done. We were over in England. We were shooting on sets. We were out in Morocco. And we were kind of separated from what was happening with the whole Star Wars business, because that was, of course, being very, very carefully controlled from an information standpoint.

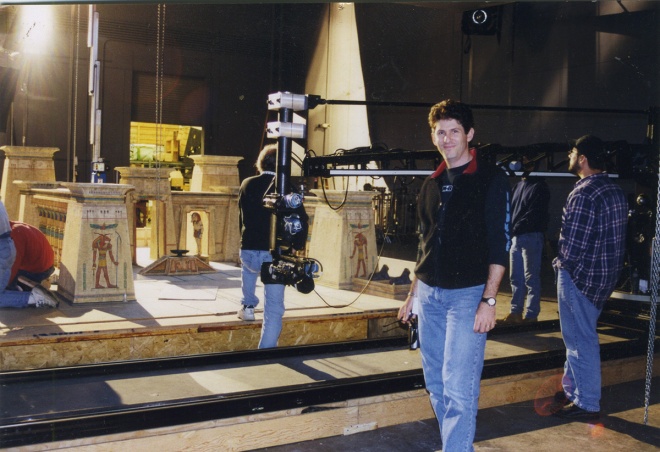

I didn’t really hear too much about what was going on with Jar Jar in terms of what they were doing with animation, but as I said, what was happening was that Seth, and Doug Griffin, and Mike Sanders on the set, they knew and they were advising us about how to do what we were doing with The Mummy based on their experiences they were having with Jar Jar. Little known fact, when we set out to do the motion capture we had just set up this whole facility at ILM to do mocap. And so, we started working out the logistics. It’s like, ‘You know, we can fly Arnold back to San Rafael, and what’s gonna happen?’ And the mocap guy said, ‘No, no, no. We’ll just pack it all up and bring it to London.’ And I was like, ‘Ooh, that’s never gonna work. All those computers, all the Vicon cameras, all that stuff. We’ll never get it calibrated. You know, it’s gonna fall out of the aeroplane and then it’s gonna be just … Oh, I don’t know.

He said, ‘No, no. Calm down. It’s all gonna be great.’ So they showed up in London with five or six crates of stuff, and they set it up in half a day and it worked perfectly. And I was like, ‘Wow, that’s amazing that we’ve got this incredibly new technology that’s capable of all this great stuff, and it’s portable and we can take it out and put it on sets so that people don’t have to travel a far distance.’ Now we’re talking about doing motion capture without any of that stuff, so we’ve progressed beyond that in a certain way. But at the same time, motion capture in a motion capture studio is still the highest fidelity motion capture you can get, and movies like The Jungle Book use it extensively in that way. And that’s because you get the best data, and it really is very portable. And once you’ve got it set up, you’ve got people that know what they’re doing, it makes its own sauce, which is really cool.

vfxblog: Let’s talk about sand in The Mummy. You had sandstorms and plenty of particle effects, and memorably they also featured faces in them. What were the challenges of doing that at the time? It must have been interesting going from concept work to, ‘How do we do that?’

John Berton Jr.: That concept work, as you can imagine, when that fell down on the table along with many other great things I was like, ‘Oh, man. That is fantastic. We gotta do that. Does anyone have any idea how that’s gonna work?’ And we had several guys who worked on that particular idea for months. And this level of particle systems, which today is paltry, but at that time was a back-breaking amount of memory usage and really uncontrollable. These are the then days Dynamation which was brand new. We didn’t have that but we had Jim Hourihan, who wrote it, so that was a good advantage. And what it really showed up was that you needed the right kind of direction and you needed the right kind of mentality for how to do it. Ben Snow gave us the right kind of direction, too.

Raul Essig was the guy that finally broke the back of it, where he just one day came and said, ‘Look, I got this,’ and we’re like, ‘Oh, okay. Here we go. Now we’ve got it.’ And he figured out how to control the parameters to get the sandstorm to do what we wanted it to do, and of course that became his life for the next six months. So he started doing every sandstorm we had. And that was something that was very difficult to come by, but once we started to understand what the size of the particles needed to be, and how many particles needed to be in each scene, and how many layers of composite was gonna be required for each one of these things, then we began to get into a rhythm of it and we could start doing really cool stuff like using animated faces.

We had Vosloo’s face scanned already, and so we could animate that and then just use that as particle emitters, and we started getting these really great results. Again, that was some of Mike Bauer’s great work, to blend in the face rising up out of the sand at very beginning of the movie. And then you get that echo of it with the giant face with the plane. That’s a great scene, one of my favourites, and just this powerful motion through space defined by the geography of Moroccan desert, and this aeroplane, which is getting scaled to everything. It was just a really, really good shot design, and then we were able to put this unbelievably complex, for its time, particle system gag into it. And it was something that was completely new. You hadn’t seen anything like that in a movie, and it was really expressive and wonderful.

But yeah, brute force all the way on that one. It was just a matter of trying to figure out how to control the uncontrollable, because I you’ve ever worked with particle systems, they are finicky. A little tiny change in one place has the butterfly effect, and everything downstream changes into something that’s different than it was before. So, art directing that is really, really difficult. And answering the bell on the art direction that you get is also very difficult. So, that was another one of those scenes where everybody talks about that scene, everybody remembers that scene, and that’s because there was something in that scene that had not been seen before. And that was because of the incredible amount of effort that people made to answer the bell on a piece of art direction that was out of bounds. It was at the fringes of what we were able to do, and that challenge was got the artists at ILM to push hard to get that to come onto the screen the way we wanted it to be.

And when you get that kind of talent working that hard on that good of an idea, you’re not gonna go wrong. You’re gonna have something that’s memorable every time. And I think that’s surely borne out by that scene. It’s an exciting scene with huge scale in it and really interesting things happening that you don’t see, you hadn’t seen before. We weren’t afraid to hang out. We were ready to cut when we had to, but we were dedicated to trying to get that stuff to live as long as it could, no pun intended, because to us, one of the big influences on the movie was, of course, the 1932 movie. And the 1932 movie is like that. It’s kind of contemplative in a certain way. And the things move at a pace which allows you to appreciate the true horror of what you’re seeing. There’s something that’s scary about somebody jumping out at you and, certainly, we weren’t afraid to exploit that in this movie.

But at the same time, this ability to say, ‘Okay, but now this is really standing in front of you,’ and accept that challenge. To me, that’s another one of these things about visual effects that I find to be really fundamental, which is that if you can stand up there when the people who think they know are watching your picture, and they’re waiting for you to slip up, or they think they know how you did it, or what kind of green screen you used, or what you painted out, or where the split lines are, and they can’t find them, that’s the highest art.

vfxblog: Interestingly, the plane sequence and the sandstorm is quite a long shot. How difficult was that to pull off?

John Berton Jr.: And that’s what we were aiming for. We wanted to be able to stand out in front of the audience with our mummy and have people be ready to cringe when it started to fall apart. Again, no pun intended. And it doesn’t fall apart. It just keeps working, and we were excited by our ability to do that. And Steve Sommers was courageous enough to put it on the frame. And believe me, if it wasn’t working, he would have cut away. And so, that’s part of what’s going there, is that we were pretty courageous with this stuff because we wanted it to prove it was real. And if you’re cutting away all the time, you can’t do it. Plus, it saves the fast cutting for the moments when you need it, and this movie utilised that to great effect as well.

One of the buzzwords around this movie that didn’t make it out into the marketing world, but might have, which was, ‘It’s not your father’s mummy.’ And to us, we were in on a big secret, right? When The Mummy was being announced, that they were gonna a make a new version of The Mummy, the reaction of Hollywood was pretty much, ‘Oh, really? I mean, how lame of an idea is that?’ There’s this guy. We know the shuffling guy with the bandages hanging all, ‘Argh, and he’s chasing you. It’s like, little can run away because he’s just too slow, right?

But, what nobody knew was that Stephen Sommers had cooked in his mind, ‘Yeah, but what if he wasn’t? What if he was a badass?’ It’s like, ‘Ooh.’ And that’s what that movie’s all about. People expected this shuffling bandaged guy and they got a badass. And that’s what made that franchise. And it’s what’s making it today, is it’s not just the walking dead. It’s something much, much more powerful than that and it’s coming for you. That’s where the speed of the movie picks it up. And when you have a chance to contemplate who this creature is in front of you long enough to truly appreciate it, and then he starts coming after you, now you’ve got something to be afraid of. And I think that’s partly what drove The Mummy to be so successful and so compelling.

vfxblog: Despite all these advancements that were made in computer graphics, there are actually a lot of live action practical effects, real plates and even miniatures in the film – can you talk about that side of the visual effects too?

John Berton Jr.: One of the things that I learned early on in my adventure in visual effects was that it’s that sort of interplay between synthetic images and reality that makes the equation work. The guys like Dennis Muren, and Scott Farrar, and those guys that had come up through filmmaking in its traditional sense, and now were embracing the computer graphics, already had that underpinning of what you needed to know about that. They were always leaning towards doing it with miniatures and these other sorts of things because they understood it and they understood the value of it.

Those of us that came in from more the computer graphics side sort of had to learn that as we went. Now, for me, I was a filmmaker before I got into computer graphics, but certainly not at the Hollywood level. But I at least understood cameras, and I understood how live action works, and how to cut and edit, and all that kind of stuff, which is probably why I’m working at a camera company now.

But this appreciation that I learned at the knee of these great visual effects supervisors at ILM was that you want to lend the live action elements credibility and image complexity to the scene. They lend that image credibility to the synthetic stuff that doesn’t have it. Meanwhile, the synthetic stuff lends spectacle back to the live action stuff that it can’t have. So, mixing these things together gives you the best of both worlds, because the live action gets the spectacle from the synthetic stuff that you can control with such incredible finesse, like the sandstorms, and you get the complexity of the real desert, the complexity of the real aeroplane, the complexity of the miniature that’s photographed that has a million tiny, infinitesimally detailed cuts and textures that come out of the materials that would take you forever to render and even describe at computer graphics is why you put together shots that are hybrids.

Above: Various concepts and rough composites for the opening Thebes shot, courtesy of Alex Laurant.

And the opening shot to The Mummy is a terrific example, because it illustrates the point so beautifully, because it’s a complete pastiche. And at the beginning of that shot, the pyramid is a matte painting, digital matte painting. But because of our ability to composite, we’re able to make that matte painting come alive, and the sun’s rising, and there’s birds flying around, and there’s all kinds of things happening in the foreground. And then you have this crane shot that comes down over the giant Palace of Thieves. And the giant Palace of Thieves is a miniature, and populated throughout the miniature are composite green screen people. There’s one digital human in that shot, but it wasn’t terribly successful. But it’s in there. But everything else is green screen humans, all carefully placed with respect to camera move and comp’ed in. The flames are a photographic element, not CG, because we’d had enough trouble with the sandstorm without doing flames also. And it was easy to shoot, and so that was something we could shoot. It didn’t have any specificity to it the way the sandstorm did, so we could shoot that.

So, you’ve got these real elements using the high-quality compositing and motion control camera to get them all to fit into the scene. So, now you’ve taken the miniature, which is good because it’s real but bad because it’s static, and increased its visual fidelity by adding in non-static elements such as the fire and all the people. So now everything’s living, and you come around the corner and there’s a wall there that’s up against the edge of the frame, and the Pharaoh comes riding down. He’s all live action, and he comes riding down with his horses, and his whips, and the whole nine yards, and comes right into the cam array. He’s as real as real could be, because he is. In fact, the wall’s real.

Above: Alex Laurant’s storyboards for the opening scene.

The wall was one of those things that, as a rookie visual effects supervisor, I was very intimidated by what I needed to do. And one of the things that I wanted was I wanted that wall. That wall is the garden of the King of Morocco, and I wanted to have the very end of the shot be real. I wanted it all to be real. And so, we had this wall that was perfect, and I wanted the Pharaoh to ride down in front of that wall. Part of it was, I’d then have to do a matte edge on him, right? ‘Cause I can use the top of the wall as a matte edge. And I don’t have to roto horses’ manes and the beard of the Pharaoh or any of that stuff. So, I had a hidden agenda there, but at the same time, it was all about creating something that was real. At the end of the shot, I wanted it to be 100% real.

And when we finally got that, they trucked in all this sand to throw down in front of the king’s wall so that the Pharaoh could ride on it. I remember the visual products producer coming up to me and going, ‘Okay, John. You got your wall,’ which was essentially, ‘You better make this shot awesome.’ So, that was motivating to me all the way through the whole movie, was to make that opening shot worthy of all the trouble we went to get it. And that, to me, that’s the way that you always get a good result, is you don’t ever assume that just because it’s easy to think about it, it’s gonna be easy to do, or because it’s easy to think about it, that it’s gonna be good. And these days, one of things that I see as a failing of the computer graphics and a failing of visual effects is that too many people say, ‘Oh, we’ll just do it in CGI.’

Above: An un-used storyboarded variation of the opening Thebes shot, by Alex Laurant.

Okay, well that’s easy to think about, and you’ll get a good result, but you’re not thinking it through long enough to really understand if there’s other opportunities that might make the movie better. That’s gonna take time to think it through. That’s gonna take time to set it up. That’s gonna take time to organise it all. And all that time gets spent in the end of the day in a laboratory somewhere with somebody slaving over a hot monitor. But you don’t see it out in the day. And I think, sometimes, you don’t get as good of a result when it’s all cooked up like that as you would if you had made some more bold choices with how you go about putting together live action composites and using the real elements in front of you that are compelling, the people, the Pharaoh’s the real Pharaoh. You see him as a person, not as a image of a person, which is sort of what you’re getting when you do CGI.

And, of course, I’m one of the greatest proponents ever of CGI in movies, obviously, but I’ve always felt that putting a strong foundation underneath it of filmmaking, and using photography to your advantage, is really, really important. It reflects on how I got into the business, and it reflects on the business I’m in right now, which is that when I got into the business, I was thinking that the Holy Grail of computer graphics was an all-CGI, feature-length animation. Toy Story, in a nutshell. And when I got to ILM in 1990 and started on Terminator 2, when I saw the live action picture on the front of a monitor for the first time … We don’t think anything about it now, but that was shocking then. Never seeing a real image on a computer screen before, and it was compelling. It was complex. It had this resonance to it that was something beyond anything that I could ever do with computer graphics, at that time anyway.

And that has stuck with me, and I stuck with visual effects. I didn’t go off to Pixar to make Toy Story. I stayed in ILM to make The Mummy, and that’s, to this day, incredibly compelling. What am I doing right now? I’m working with how to put live action into virtual reality. And yeah, sure, it’s easy to do a, well, it’s not easy. It’s easy to think about doing it with a game engine and just … Call of Duty, or Halo, or whatever is very immersive. You can go wherever you want, and all the parallax works and everything. But when you start to do live action, you suddenly lose the ability to have that realism that virtual reality gives you when you can move anywhere you want and everything lines up correctly in perspective and parallax.

What we’re doing at Lytro is solving that problem, and that’s the same game again. Let’s figure out how to take the complexity of live action and put it into this incredibly compelling world that, at the moment, live action doesn’t work so well with. So, it’s the same problem looked at from another angle, but that’s the progression from The Mummy to today.

And those kinds of lessons ring through, all the way through, whatever movie you’re working on. The number of lessons that I learned making The Mummy, and The Mummy Returns, and the Men in Black pictures were incredibly influential on movies that I worked on such as Charlotte’s Web, which you would think, ‘Maybe there’s no crossover at all,’ but there’s so much crossover. It’s just the creatures are cute instead of scary. But you still have to put the same amount of effort into it, because you have to same level of believability. If you want people to be charmed by Charlotte, it’s the same technique that you use to make people be afraid of the mummy. And that’s the same combination of realism and spectacle from the synthetic pictures.

vfxblog: I just wanted to finish by asking you about one of my favourite sequences in the film which is when Brendan Fraser’s character takes on all those mummies in one long shot? How did you orchestrate that, both on set and in post?

John Berton Jr.: Well, that sequence, of course, was also one of my favourites. And how that sequence came about was that we originally wanted to do something that was evocative of Ray Harryhausen. And so, we looked at a lot of the stuff on Sinbad, and Jason and the Argonauts, and all those famous fight scenes, and we tried to figure out how we could so something like that, with a lot of art direction and sketches.

And we worked with Simon Crane, the famous action director, to work out what we called the kata, which is the action sequence. And we spent weeks working that out and then training stuntmen to perform it. And once the stuntmen all had it down and they could perform that, then we brought in Brendan and taught it to him. And Brendan’s a brilliant physical actor, and he knows how to do these kinds of things. And we gave him as much help as we could to have him have a real weapon that he could wield so that he had the right motions in his arms. And we had stuntmen that grabbed hold of him when necessary to give him the right kind of balance for the sorts of things he was imitating that he was doing. So we gave him every opportunity to succeed, we hoped. And of course, Brendan … You can’t say enough good things about his dedication as a performer.

Above (and further, below): Alex Laurant provided vfxblog with these sketches that were produced for the fight sequence. The sketches were made by Laurant and by the art department creative director Mark Moore (where indicated).

He really sunk his teeth into it and really went after it, and when it was time to do that shot he really for it, as you should do of course. He’s a trained professional, as they say. And he really made a great performance. We shot all of the actors, all the stunt guys in with Brendan, as reference first. So, we shot the whole thing with Brendan and the 13 guys, and then Brendan did it by himself after we’d shot the reference with the 13 guys. So, the 13 guys, of course, were reference for the animators. We also went and motion captured them, in order, based on the performances that they’d done on the day, and then it was all assembled. And then the animators had to go in and do the special things that the motion capture couldn’t capture.

And we worked it all out from that standpoint. It was all surrounding Brendan’s performance. So, we set it out to be a winner from the very beginning. It ended up with a couple of cuts in it, only because cinema demanded it, but it was a winner in its concept and it was a winner the way we shot it. And it reads as a winner when you see it in the movie. And I couldn’t be more happy with the way that that all turned out, because again, the amount of preparation, that was the thing. Nobody phoned it in. We spent a lot of time making sure we knew exactly what was gonna happen in the fight scene. A lot of people spent a lot of time rehearsing it, even though they would never, ever be on the frame. They spent a lot of time rehearsing it so that Brendan’s performance would be as good as it could possibly be. And then, Brendan spent a lot of time trying to learn it to make it exactly right. Then we followed art instructions and we did it exactly the way that we planned to do it.

Above: In relation to the fight scene, Laurant tells vfxblog that Stephen Sommers “had been re-conceiving the scene, and found himself wanting ideas for humorous fight gags that could inspire his stunt choreographer, in the spirit of Raimi’s The Evil Dead. Being that we’d all previously sorted out that the soldier mummies were all filled with dusty undead sand, this gave us free range to mangle them this way and that without mercy nor worry about maintaining the PG-13 rating; so, we laid into this challenge with gusto, and these sketches were the result. A few of those gags ended up making it into the final sequence, either fragments thereof or in one or two cases wholesale.”

And when we got it into post, then we had every advantage to make it good. And we took advantage of that and we did some great compositing, again, with live action elements, synthetic particle sand elements, which we knew a bit how to do now. We could get the sand to fly off of Brendan’s sword by match-moving the sword. All kinds of great stuff went in to polish that shot off, because every day we worked on it we saw how good it was gonna be, and we just kept adding more stuff onto it to make sure that it was worthy of all the effort everybody had put into it. The end of that story is that, five or six years later, I went to see a presentation by Ray Harryhausen about the work that was done on Jason and the Argonauts and Sinbad. And he described the process that he used to make those famous scenes where Jason fights the skeleton, and it was exactly the same process that we had used.

I was so proud of the fact that we had figured that out on our own in a certain way, and that it was exactly the methodologies that had been used to do the original. And so, I just thought, ‘Well, we were on the right track. We were on the right track to make a good shot, because we followed the instructions even though we didn’t even know what they were.’ And the whole business of training the stunt guys, and having the main actor fight against the stunt guys, and putting it all together in the edit with the stunt guys in it, and then taking the stunt guys out and putting in the skeletons. That’s exactly what Ray Harryhausen did. And that’s exactly what we did. And so, it’s an homage to Ray Harryhausen’s terrific work, not just in image, but, in fact, in execution. And that’s what I’m proud about.

Above: As an example of one of the ideas that made it into the final sequence, Laurant details how he sketched “Brendan Fraser laid out in mortal peril from one soldier mummy approaching from above (wielding a huge tombstone), and meanwhile the just-dismembered hand of another soldier mummy crawls up next to him, blindly going for the sword that is conveniently lying there; Brendan resourcefully grabs the mummy-hand-holding-the-sword, and uses it to off the first attacker.”

Thanks to John Berton Jr. for participating in the interview, and to Alex Laurant for providing the incredible imagery.

All images © 1999 Universal Pictures and ILM/Lucasfilm Ltd.

Post a Comment