Beauty story for Kingkong magazine http://www.kingkongmagazine.com/fashion/ophelia/

Bright Opener

Posted in: Animation

Download AE project https://videohive.net/item/bright-opener/17361621?ref=3uma

The Master: How Scientology Works

Posted in: Animation

Get a free 30 day trial of Audible here: http://www.audible.com/nerdwriter

I WAS NOMINATED FOR A SHORTY! VOTE FOR ME HERE: http://shortyawards.com/9th/theenerdwriter

NERDWRITER T-SHIRTS: https://store.dftba.com/products/the-nerdwriter-shirt

SOURCES AND FURTHER READING:

Why Scientology auditing is not at all like traditional psychotherapy (part 2).

Why Scientology auditing is not at all like traditional psychotherapy (Part 1)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dbmPVq6e2aA

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3856510/

Folding the world record paper plane

Posted in: Animation

John Collins, who designed the distance world record for paper airplane flight, presented a workshop for students in the master’s in design engineering program, a joint program of Harvard’s Graduate School of Design (GSD) and School of Engineering and Applied Sciences. After the workshop, held at the GSD, Collins demonstrated how to fold his world record plane.

The ACLU Dash Button

Posted in: Animation

I built an Amazon Dash button that donates $5 to the ACLU every time I click it, allowing an immediate, physical response when I read news of further assaults on our civil liberties.

More details at https://medium.com/@nathanpryor/the-aclu-dash-button-16719e446363

The Loch Ness Monster is one of our most enduring myths. People have sought to uncover ol’ Nessie’s secrets for 1,500 years. But only one man has devoted his life to learning the truth … and living alone in a van by the loch to do so. Meet Steve Feltham, Nessie’s full-time watchman since 1991.

SUBSCRIBE: https://goo.gl/vR6Acb

This story is a part of our Human Condition series. Come along and let us connect you to some of the most peculiar, stirring, extraordinary, and distinctive people in the world.

Follow us behind the scenes on Instagram: http://goo.gl/2KABeX

Make our acquaintance on Facebook: http://goo.gl/Vn0XIZ

Give us a shout on Twitter: http://goo.gl/sY1GLY

Come hang with us on Vimeo: http://goo.gl/T0OzjV

Visit our world directly: http://www.greatbigstory.com

Richard Vs Barack

Posted in: Animation

Challenged President Barack Obama to a kitesurf vs foilboard learning contest – here’s what happened https://virg.in/ZWz

109-Year-Old Veteran and His Secrets to Life Will Make You Smile | Short Film Showcase

Posted in: Animation

Meet Richard Overton, America’s oldest veteran. In this lively short film by Matt Cooper and Rocky Conly, hear the whiskey-drinking, cigar-smoking supercentenarian reveal his secrets to a long life.

➡ Subscribe: http://bit.ly/NatGeoSubscribe

➡ Get More Short Film Showcase: http://bit.ly/Shortfilmshowcase

About Short Film Showcase:

The Short Film Showcase spotlights exceptional short videos created by filmmakers from around the web and selected by National Geographic editors. We look for work that affirms National Geographic’s belief in the power of science, exploration, and storytelling to change the world. The filmmakers created the content presented, and the opinions expressed are their own, not those of National Geographic Partners.

Know of a great short film that should be part of our Showcase? Email SFS@ngs.org to submit a video for consideration. See more from National Geographic’s Short Film Showcase at http://documentary.com

Get More National Geographic:

Official Site: http://bit.ly/NatGeoOfficialSite

Facebook: http://bit.ly/FBNatGeo

Twitter: http://bit.ly/NatGeoTwitter

Instagram: http://bit.ly/NatGeoInsta

About National Geographic:

National Geographic is the world’s premium destination for science, exploration, and adventure. Through their world-class scientists, photographers, journalists, and filmmakers, Nat Geo gets you closer to the stories that matter and past the edge of what’s possible.

Meet Richard Overton, America’s oldest veteran. Born on May 11, 1906, he has celebrated 110 birthdays (109 at the time of filming) and counting. The supercentenarian has lived through the Great Depression, served in World War II, and witnessed the rise of the Internet. From the Ford Model T to self-driving cars, more technological and scientific progress have occurred in Overton’s lifetime than perhaps any other century in history.

The whiskey-drinking, cigar-smoking elder reveals his secrets to longevity in this lively short film.

https://www.overtonfilm.com/

Want to help Mr. Overton stay in his Austin, TX home? Donate to his home medical care expenses on GoFundMe.

https://www.gofundme.com/Help-Richard-Overton

Credits: Matt Cooper (director, producer); Rocky Conly (cinematographer, producer); John Halecky (producer).

109-Year-Old Veteran and His Secrets to Life Will Make You Smile | Short Film Showcase

National Geographic

https://www.youtube.com/natgeo

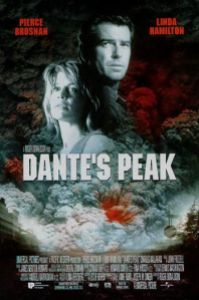

Today, many of the visual effects in the 1997 disaster flick Dante’s Peak would probably be done completely digitally. Pyroclastic flows, exploding buildings, bridges and cars being swept away by a torrent of ashen river – these are things that can be done with complex effects simulations, CG elements and masterful compositing.

But two decades ago, the techniques were still in their infancy, and a hybrid approach to realising such shots involving miniatures, practical effects and then augmenting with digital techniques, was just emerging.

Dante’s Peak, directed by Roger Donaldson, took advantage of this approach by incorporating some of the most convincing miniatures ever put to screen – especially for the river and bridge scene – and using nascent digital effects tools to add even more layers of realism. The work was realised by Digital Domain as well as a host of other modelmaking studios and digital effects houses.

Dante’s Peak, directed by Roger Donaldson, took advantage of this approach by incorporating some of the most convincing miniatures ever put to screen – especially for the river and bridge scene – and using nascent digital effects tools to add even more layers of realism. The work was realised by Digital Domain as well as a host of other modelmaking studios and digital effects houses.

To celebrate the film’s 20th anniversary, vfxblog spoke to overall visual effects supervisor Patrick McClung, then at DD, about the hybrid effects in Dante’s Peak, how the decisions about miniatures were made, and how the only slightly related Volcano film heavily influenced production.

vfxblog: When you came on board, it was still the early days of CG and Digital Domain was clearly still doing great miniature work. Was Dante’s Peak always planned as a hybrid mix of the techniques, or was the director or studio pushing a certain approach at all?

Patrick McClung: Well, going back a bit, the visual effects industry has always just used the latest techniques if they’re applicable, you know. And one of the big problems with visual effects was optical compositing, and you could see on our old TV shows and so forth where sometimes the shots are very contrasty and have bad edges and mattes and blue lines around people. And that’s always been a very difficult process. And painful and expensive. When I was at Boss Film toward the 90s, digital compositing came in and that sort of revolutionised everything. All of a sudden you could get much better composites. So everybody jumped on that because it was affordable. And you had a lot more control.

Then with CGI, the computer generated imagery was rolling. And ILM was on The Abyss and had done what we called the ‘Water Weenie’, the big water tentacle, and that was a very expensive proposition. They were just barely able to do it back then. And then later they did Terminator 2, and so as the software got better and less expensive and the equipment got less expensive, things became available to more and more other companies.

So at the time I did Dante’s I just looked at what had to be done and I made a decision as to what to do, and the studio – they really had very little to do with it. The director Ronald Donaldson was on board with everything. One of the big problems I guess back then was the pyroclastic flow, the big cloud of ash. There was software to render these big clouds – it’s called volumetric rendering – but it really wasn’t ready. We tried it at DD and it would take like a week to render something, and you look at it and go, ‘No that doesn’t look right.’ So I made the decision to do that stuff practically.

I had a pretty good knowledge of the processes, what we could do digitally. Also, Digital Domain had a certain amount of work that was going through there, with Titanic coming in and The Fifth Element, which took a lot of resources. And so a lot of what I had to do was take some of the shots to other companies to do the compositing, because DD was so busy. I would approach it very differently now because of the technology.

vfxblog: The benefit of having so many miniatures in the end did seem that it gave the film so much more of a visceral feel. Is that how you felt, did it seem to work for this style of film?

Patrick McClung: Yeah, yeah, I agree. And, you know, in contrast to Volcano, that film was more lava. That was their thing. Roger Donaldson was a geologist and when he got the script for Dante’s, he wanted to be as accurate as he could to what events would happen, and it was patterned after Mount St Helens. So that really lent itself to miniatures, explosions and things blowing up. We just couldn’t have done it back then digitally, not with the time and the resources. Just a lot of that software just didn’t really – it existed but was in a cruder state.

vfxblog: It’s funny, a lot of people think that they pyroclastic cloud work was digital, but it was basically practical, wasn’t it?

Patrick McClung: Richard Stutsman was one of the special effects supervisors. Richard was really good at this stuff, and we knew we had our hands full with this film, so I said, ‘How about just shooting some sort of powder out of air canons?’ And as it turned out on this movie Chain Reaction that I had worked on before, the special effects person on that movie was a gentleman by the name of Roy Arbogast who went back to Jaws. And Roy had these giant air cannons. These things were three feet in diameter. They’re big air tanks, basically. I think they were like twelve feet long or something like that. They were enormous, I’d never seen them this size, and he had to knock down a little building with them on Chain Reaction. I was pretty impressed, so as it turned out Roy was on Dante’s Peak. And I asked Roy about these air canons and he said, ‘I have five of them.’

We shot out near the Palmdale Airport and we had these big cylinders sort of pointing upward, and that’s stuff that Richard arranged. The first thing that came to mind was fuller’s earth – it’s actually ground up clay and it’s very light and we’d have to tint it, and I also thought about powdered concrete. But Richard said it was fairly acidic and it would be a cleanup problem. And so he came up with this material that I’d never heard of called Bentonite, and it’s used for drilling oil wells. It’s a type of fuller’s earth, it’s ground up clay and it’s very dark. It’s charcoal grey. And it’s mixed with water and pumped down to the drill head, and basically it’s like a lubricant.

But when you buy it it’s powder and it was really dark. It was perfect for what we had to do. And every time we were shooting these air canons off I think he was using like six hundred pounds of this stuff, and because it in essence was dirt, it could fall on the ground and we didn’t have an environmental hazard on our hands. We were shooting at about 250 frames a second and the stuff would shoot up maybe a 100 feet in a couple of seconds. It was pretty impressive.

vfxblog: One of the things about the way some of the pyroclastic cloud appears in the film and even when it’s off in the distance is that it’s so well integrated in the shots. And I think that is testament to the digital compositing even back then. Can you talk about some of the challenges of that?

Patrick McClung: Well, you know, back then again the whole digital thing was fairly new and it was hard to find people that were versed in this software. It was very hard, there weren’t a whole lot of people. And so my big fear starting on the show having done just two small shows because there was Titanic and Fifth Element in front of me that they would sort of just grab everybody, and indeed that’s what happened. So some of the shots were done there at Digital Domain, some were done at various post-production houses in Los Angeles. A lot of those houses are gone now, gone out of business.

But it was just a person with a very good eye, and because we were doing these pyroclastic clouds outside we had a nice contrast between the sky and the clouds, and the clouds were pretty dark and the sky was pretty light. So you could pull a luminance matte from it, you know basically make it, it’s like shooting almost in front of a blue screen or green screen. And it was just a lot of finessing the composites because some were behind people, which were not too happy, and trees and what have you. So it would be you know making, generating mattes from skies and then hand-rotoing basically, hand-drawing mattes around people and so forth.

And I was pretty new at all this stuff so I just had to depend on our compositing supervisor for Digital Domain, this guy named Price Pethel who was extremely good at this. So Price was the guy who was shepherding all of this. We’d do something and film it out, look at it, and that was, back then it was, that was a process to record it on a negative and then take it to the lab and then process it and then get film back to look at it. That was a twelve hour turnaround, and so what you see on the screen is not necessarily what you get on the final film out, so it was always sort of a big surprise. Sometimes it would not look all that great on screen, but it would look wonderful on film and vice versa.

vfxblog: Another thing I remember was the huge volcano miniature made for the film. But I’m curious about the development of that, because I remember reading it didn’t actually make it into the final film, and that it was a matte painting instead.

Patrick McClung: Well in everything I’ve done and every film I worked on is a model maker, you know, all the way up to everything recently, when you’re going to figure out a show it’s your best guess on what you think will work and what won’t work. And in everything I’ve ever done, I think that might have been my biggest mistake was that stupid volcano. So the director Roger Donaldson wanted this volcano to be almost on top of the town. Those mountains were based on Mount St Helen, those are all ancient volcanoes, they’re all like a cone, you know? A cinder cone. And when you get up and you look up at them you lose all that mountainous feel. I went, oh crap.

We shot it and it just didn’t look very good, oddly enough. So that’s why the painting is a huge cheat. We did use some of it, some of what we shot. We actually got back a little ways and shot the miniature, which is a giant miniature, but that was one of those things that didn’t work out. A gentleman by the name of Alan Faucher ran the model shop. Unfortunately he’s passed away but he did an amazing job.

vfxblog: Where was that volcano filmed?

Patrick McClung: The Van Nuys Airport had a big open area and lots of hangars and so forth and actually, they were filming – across the runway – they were in hangars doing Air Force One. And then we had the other side of the airport, we had a big, huge open area of tarmac. And two hangars and then two other buildings for shooting stages. I think they built just a big gigantic wooden framework and it was huge blocks of Styrofoam, you know polystyrene, which comes in really large blocks.

And they used hot wires to cut it. They’d string it and it looks like a big yoke and they would just, you could cut it and sort sculpt it. And so they made in essence like a conical section out of wood with plywood and then they just put the thinner sheets of this sheet styrene on the outside and then sculpted it basically. It wasn’t a technically advanced method. It was pretty straightforward, you know, but it was just done very artfully and done extremely well.

vfxblog: Let’s talk about the bridge miniature, because that is probably remembered as one of the most spectacular pieces of effects work in the film. Was that also filmed at Van Nuys?

Patrick McClung: Yes, we found a big piece of property and we had our offices there, we had the model shop there, we had the shooting stages there, and then we had this big huge open area. We had an art director by the name of George Trimmer, and George figured out the whole layout of this model, with Richard Stutsman. And then Richard brought another guy named Dean Miller who handled all the water bits – the tanks and the pumps to pump the water back up.

What we had were two large steel tanks and one of them was up forty feet in the air. There was a giant hydraulically powered door that would tip down like something in the back of a truck and allow the water to spill out, and it would go down this spillway into our miniature valley and then the water would end up in another tank. And then we had this huge pumping system to pump the water back up. I think it was probably the biggest miniature of that type ever built. Because it was enormous. We also had another section off the main tank that would feed the dam, the dam miniature. Because it was all sort of built into one, you know, one big unit. We only shot the dam the one time because we just literally did not have time to rebuild it and shoot it because time was so short to get that all done.

vfxblog: You really were under the clock on this one.

Patrick McClung: We were on twelve, fifteen hour days seven days a week. It was just an insane project. One day I sat there and counted the amount of shots we needed of that flood for the storyboards and so forth and we actually didn’t have enough days scheduled to shoot everything. And we figured ways around it, but if you notice in the movie once the volcano starts erupting it’s all very overcast. And so, because this town they found, Wallace, Idaho, was in a valley when we were shooting in the summer, the sun would go down over the hills and we had, and we had another three or four hours basically before it actually went down because we were in a hole, in a sense. And so we had three or four hours of diffuse light, magic hour basically, to shoot in.

So by the time we get to shooting the miniatures, now November December I think, and the days were short, and so we positioned the miniature so the sun would travel across the top of it so we could shoot in the morning when the sun was low before it came over, let’s say, the left edge and lit the right edge. So we would shoot in the morning until the sun was too high and then we’d wait until the evening where it was the same, you know, just the opposite position where there was sort of enough exposure to shoot but the sun was now lower on the other side of the valley.

vfxblog: What was that like trying to get all the shots done in time?

Patrick McClung: Well, we just had to find ways around it. When the Humvees jump over the other side of the bridge as the bridge is collapsing there was almost no set there. It was a green screen. We shot that back in LA. But we needed to have trees back there so I thought, well, what we can do is just shoot different sections in tiles and put them all together and have background. So that’s what I did. I brought a still photographer out. He just shot horizontally and vertically, and then there was a company called CIS that did the composites and they sort of stitched them all together into a background. So because we could do that, that actually gave us some breathing room.

vfxblog: What was the toughest thing about the bridge shots?

Patrick McClung: Water was the big issue. And when it was being designed we had a certain size and it was all, and it was up on scaffolding. Let’s say the bridge itself was probably fifteen feet off the ground, you know, and it was all sort of sheathed in plywood. And so I’m looking at it I’m thinking oh, because we were going to do it a quarter scale and I’m looking at it going, I don’t know… And I go talk to Alan Faucher and say oh you know, we hadn’t built the vehicles yet. You know, and the bridge itself hadn’t been built yet. And I talked to Alan and I said you know I don’t think quarter scale is gonna cut it. I think they need to be bigger. So we went back and forth and third scale was too big. We’d made the river, the river was already in essence built. We had a certain finite width. And so we went between quarter and third scale. So the vehicles are bigger than quarter scale. And I used to have this sort of thing where somebody would ask me how big something should be and I’d just hold my arms out at arm’s length, you know, about this big which was seventy two inches.

So anyway we sort of came up with this in-between scale that we nudged them larger and I think that really helped. Because quarter scale, when I was on Aliens we did the queen and power loader sequence, the big fight. That was quarter scale and it was because we didn’t have more money to do, we wanted to do it larger but we just didn’t have the money because that meant building bigger sets, and you know miniature sets are expensive. You know, more expensive than full-size sets believe it or not.

So we had this sort of compromise of larger than quarter scale and I think it really helped. So talking to Stutsman I said you know can we tow these vehicles from a centre track? And so he worked all that out. So there’s actually a centre track in there with a cable pulling the vehicles, all three of them. So that’s how they’re motivated. If we did it radio controlled you’d never know. They could slip off.

The water in that thing was only maybe a foot deep at its deepest. And we had built all kinds of rises and falls under the terrain to get the water to look like it was uneven. But it was a large volume of water. I can’t remember if it was seven or eight hundred thousand gallons, but it was moving and we would empty that I think in five minutes. It was some phenomenal amount. And then there were the layers of people that were dumping debris in the water, and we had built a whole house that went through and smashed into the bridge.

vfxblog: How did you work out what all this might look like, as in, for reference of a volcanic event and a river?

Patrick McClung: We had two volcanologists and they were very helpful. And I had a book on volcanoes. And I read about the lahars, it’s really just a slurry of ash. I’ve heard it likened to liquid concrete. When Mount St Helens exploded it melted all the ice and snow, because there was permanent ice on the top of the mountain that would never melt. So the heat melted all of that and the whole thing is made of ash anyway, the whole mountain in essence. And so you had this big flow of this grey colored water.

They found a colorant for the water, this sort of grey powder. For the right scale, we overcranked the cameras to 48 frames a second. And it slowed the water down a bit. Just looking at it again, it looks a little miniature-ey but it holds up pretty well. The set was a forced perspective if you look at it going back, you know the trees shrunk in size going back, you know, the length of the model. And the trees at the back were probably eight inches tall or something like that. Just to give us a distance to the model.

vfxblog: Anything people should look out for in that sequence?

Patrick McClung: There the van and there’s this character Paul Dreyfus – he doesn’t get over the orange van – you see the wheels spinning. So I’d asked Stutsman if we could do a spinning wheel shot. The director didn’t ask for it, I just decided we needed that shot. Those tires were the size of your hand. Smaller than that, the size of your palm. They weren’t very big. And he hooked up a little thing, a little smoke generator. And you see the wheels spin, and in sound effects you hear the screeching tires, and it looked really good. Just watching it I was surprised at how nice it was.

One thing that’s part of visual effects is you have to think like a filmmaker, and I told Roger I said we need a shot of a structure of the bridge breaking, you know, just snapping. And he said yeah let’s do that. Because you know what usually happens is shots are boarded, or storyboarded very specific, and sometimes you need little inserts. And so I just think of movies I’ve seen before that have live events and you always have a little close-up of something fracturing. So we did one of those things, you know, with the steel frame under the bridge.

vfxblog: How many takes could you do of the bridge sequence?

Patrick McClung: We’d do it in the morning and evening. We had only so much water we could release, and we really couldn’t pump it back fast enough for the morning shoot to get another go at it. So we had to really plan what we were going to do. As we were going to open the floodgates, so to speak, everything was ready and we get the water flowing and all the debris going. And we do the shot and we’d close the gate. And we’d still pump the water up, it was still constantly going. So we could do it for about three takes each time from memory.

We had enough water and everything, and at some point if there was just too much water that had been depleted it’d take a couple hours to actually pump it back up, it was actually pretty fast. But the sun would be up at that point, the sun had risen far enough that it started lighting the opposite side of the terrain. So we’d pump the water back up and reset for the evening, and do other shots. You know, other stuff inside and what have you. And luckily they were short days, it was winter, so we could squeeze it in. And we went right to the last minute.

And unfortunately the shot where the bridge finally rolls over with the van, I really wanted to do it again but we were quite literally out of time. Because that was redressed to look the opposite way. If you looked at the bridge and look to your right you’d see this whole valley going up away from you. You look to the left and it just ended right there. And so what we did is we did all the shots are looking up the canyon first, and then we redressed the whole model to look the opposite direction. And that was a big deal. And so by the time that happened we didn’t have a lot of time to shoot you know the bridge rolling over.

And what Richard Stutsman had to do with the bridge, which is a brilliant idea, he figured this all out. He had hydraulic rams that could control the bridge because, even though the water’s only six inches to a foot deep in a lot of areas, there’s a lot of hydraulic pressure from the water on the bottom of the bridge. Because most of the surface of the bottom of the bridge was in contact with the water. We had these major hydraulic rams under the bridge to control it so we could make it do whatever we wanted to. So that was a really smart move because we could reset the bridge at a moment’s notice. And when it actually sort of flipped and rolled over we had a little puppet, you can see the puppet go flying over Dreyfus, his character in the van.

vfxblog: It all seems to break apart really convincingly – was there something you were doing there?

Patrick McClung: We used a lot of snow plaster. It’s been around forever. I think it goes back to the Romans. It actually foams when they mix it together, and when it sets it’s like a sponge. And so there’s no strength to it and they’ve been using it in the movies forever. You know, when somebody punches through a wall, it’s snow plaster. So a lot of the bridge was solid except for the areas we knew we were going to break away, and that was all done with snow plaster and then all sort of feathered in so you couldn’t see the joins.

And there were pyro elements in there to blow things apart because that’s what happens when something large breaks, it just, you see debris fly all over the place. And so I think we had a dozen cameras on it and I actually missed it. I was driving back from one of the post companies and everybody was out there, Roger Donaldson, Ilona Herzberg, the producer, Gale Anne Hurd, everybody was there, and I just missed it. I just drove up and I hear this cheering and you know Gale came down. And I knew Gale from Aliens, she said oh it was fantastic and great. Okay, guess I’ll see it on the film.

vfxblog: Any other miniature shots from the film you wanted to highlight?

Patrick McClung: There’s the shot where it’s a wide shot where you see the truck, the family, driving down the road and the pyroclastic flow is behind them in the distance, sort of landing. What I figured to do on that one is that the truck is actually pretty small. It was maybe a foot or foot and a half long, I don’t remember, and again it was on a track. We had a whole miniature of the town that we built that was a fairly small scale but large because it was a big open area. And so I thought, okay we’ll shoot this motion controlled so we can shoot the town and the hills behind it separately, and the car was a different scale so we just put that on the ground somewhere in the stage and just made a little path about four feet wide of just, against black I guess or greenscreen.

We shot that separately and then we shot the buildings that were closer to the camera, larger scale buildings, we shot those separately because I knew those buildings would be, the small buildings wouldn’t hold up scale-wise. So it was a pretty involved composite. I think we needed one more pass on the compositing because the edges are a little crisp, you know, when the flow comes over the hills. But we were out of time, that was like, it had to go in the movie. We just ran out of time.

vfxblog: What I remember about that shot after the car swings past camera is, I particularly remember on the big screen the following shots of all the houses splintering and whatnot.

Patrick McClung: I don’t know what scale they were but they were probably two to three, four feet high. Again they were plaster and snow plaster and they were just loaded with these air cannons, you know the smaller ones that are probably three feet long, and so we had these very high pressure air canons and then just primer cord. And bombs and what have you to just blow the crap out of them. And those were shot at 120 frames a second, to slow them down.

vfxblog: There were some freeway shots done as miniatures too, how were they achieved?

Patrick McClung: We farmed out the freeway to Grant McCune. They built cars and the collapsing freeway. Production had built a section of it in Wallace, a little piece of the freeway, and we put a greenscreen up and added the miniature freeway collapsing behind that. There’s also a shot of a semi getting blown apart.

vfxblog: There were a few CG lava shots and of course digital compositing work – can you talk about those?

Patrick McClung: It wasn’t a predominantly lava-laden show. We didn’t have much of it. But the first time you see anything like that it’s sort of a geyser of lava. And what that was, it was just sand. We shot it inside. It was just white sand lit with a white light. And we color-corrected it red. And it worked extremely well, it looked like a geyser of lava. And there was CG lava below it and it was on a miniature set we had built, the little piece.

Then there was the grandmother’s log cabin which they have to escape from. They had built the interior of the cabin up in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho and we started talking about how are we gonna do the shot where the lava pours through the wall? And I had them build the set so they could take the entire back wall out of the set and have a greenscreen there, which we did. We shot that at midnight. And we removed all the furniture so it was a Steadicam shot. So if you could see the original plate, everybody would be walking down and the back wall would just be green, with no furniture.

And so when the director called ‘lava’ they turned on interactive lighting on the set, to light it red. And so what we did back in LA is we rebuilt the set, not even half scale or maybe it was full scale. It was a very small set. And the CG guys did a digital tracking of the shot and converted that to motion control files. So we had a motion control camera that would reproduce that Steadicam move. So we shot all these elements of part of the whole back wall, and we made a big battering ram that was backlit with green, so when you’d see it pushing through the wall it was basically this big green tongue.

It would smash the wall and that would allow the CG lava to pour through and it would look like the wall was reacting to the lava. And then we shot furniture that was on wires that was painted with something that would burn instantly that Stutsman came up with so it looks like the lava is pushing the furniture back. And then we had like a rug hanging from the wall and that was shot separately. So it was an incredibly complicated shot and it came out great.

When they come out of the log cabin, we shot that in a big piece of property inn LA called Agua Dulce near Vasquez Rocks. They re-built the cabin up there because by the time they come out now the lava’s flowing on either side of the cabin. Roy Aborgast had built trees that were piped with gas so he could just turn them on, light them up so it looked like all the trees were on fire, and the path where the lava was gonna flow was just a trench cutout and they put in lighting with red gel for interactive light, the lava light basically. And the trucks were on big movers, hydraulic movers, so they looked like they were sort of floating. And so they come running out and they see the lava flowing. So there was nothing there basically, so that’s digital lava.

And then when they go down to the boat, the boat was shot at Falls Lake at Universal Studios. It’s a lake with a big backing, a two hundred foot wide backing. And so we shot a lock off of the burning house with the lava, and then it was put in behind the family in the boat in the water at Universal. So it was just a little of everything.

And if you watch the making of they talk about this boat flipping over, and you know I was obviously there when that happened, and we were at night so we had this giant greenscreen lit up fifty feet high and two hundred feet wide, and had this whole lake lit up. And what they did with the little metal boat is they bolted the bolt to a Zodiac that had the camera and motor on it. So it’s one unit.

And when they took off, this is the first thing of the night, first time we’re shooting up there, what happened is I could see it, the water churned up from the motor swamped the little boat. And the whole thing sort of rolled over out there. It was pretty scary but the safety divers went out there and rescued everybody.

So what they did is they said okay well what we’re gonna do is just go and shoot all the close-up stuff. And what they did is they went up to a higher point in the back of Universal. Universal’s a big piece of property. They put the boat on a tabletop with inner tubes on the boat so they could rock it back and forth and do all the close-up dialogue where they’re talking about the boat and all that. And then they did that couple of nights and then we came back and shot the wider stuff when they figured out the rig.

vfxblog: What impact did the release of Volcano have on any decisions about how to do the effects?

Patrick McClung: Well that was going on at Fox, and both the studios [Dante’s Peak was released by Universal] were trying to outdo each other with their release date. They kept backing their dates up trying to get ahead. And usually if two similar movies came out in the past one studio would shift their movie to, you know, the other end of the year. But both the studios, I call it a pissing match, kept sliding their release dates.

And there came a point when – and remember this is the first movie I’d supervised and it was enormous – all of a sudden they came up with a date that essentially took about half our post-production time away. And I wasn’t even sure if it was physically possible to do the work that we had to do in the time. So we had a really aggressive schedule to finish everything.

Read more retro vfx articles on vfxblog.

Players can now use their World of Warcraft gold to purchase virtual goodies in Blizzard’s other games

Posted in: AnimationBlizzard Entertainment is famed throughout the gaming world for multiple games of theirs. From RTS (real-time strategy) to MOBA (multiplayer online battle arena) to open-world MMORPG, the studio has it all. They recently ventured into the FPS (first person shooter) with their smash-hit, Overwatch.

Now, the company behind the famous MMORPG, World Of Warcraft (WoW) has announced that players can transfer their gold earned in World of Warcraft into virtual goods, and buy items in other games of the company like Hearthstone and Overwatch.

Here’s the video released by the company to further elaborate the whole process:

The WoW tokens were initially introduced back in 2015, which allowed players to buy more game-time with gold earned by them in the game. Players can purchase WoW tokens through gold and trade them at a respective marketplace.

Now with gold that can be converted into Battle.net credit, players who feel they have enough gold in WoW or have high class gears that they no longer use, can exchange it for credits and use it to buy lootboxes in Overwatch or card-packs in Hearthstone.

By this move, the developers ensure the liquidity of players through different games on their platform and not just stick to one.

The post Players can now use their World of Warcraft gold to purchase virtual goodies in Blizzard’s other games appeared first on AnimationXpress.